Summer 2021 Field Research Fellow — Doing Research on Asia during the Pandemic, Part II: Online Databases

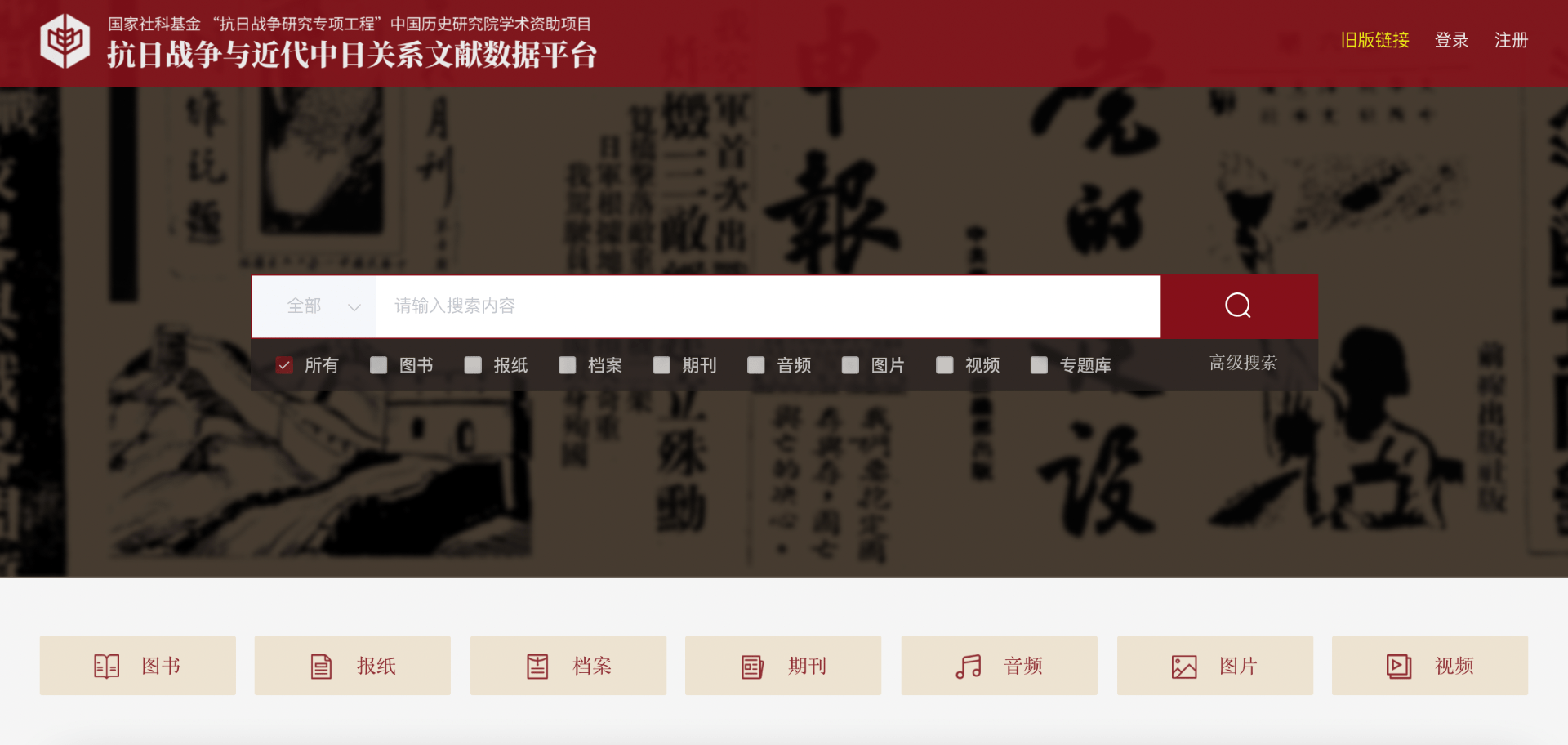

The Covid-19 pandemic has brought enormous difficulties for doing research on Asia. Since in-person visits to archives and field work has become more inconvenient, this blog post explores alternative ways to do research. Based on my experiences of using the “Data Platform of Documents on the Sino-Japanese War and modern…