A few weeks back my team and I were announced as Finalists in Taiwan’s international Presidential Hackathon. We were selected for our digital platform, known as Madaster, which creates a digital ledger of all the building materials existing in designated infrastructure. In July 2019 we will be meeting with the president of Taiwan as well as various ministers and CEOs of Taiwan’s leading environmental and technology institutions to demo our platform and compete with the other five finalist teams from across the world. I’ve received countless requests to share our Hackathon application, so in the spirt of the event’s focus on open-data and civic responsibility I am posting our application publicly below. But first, I must explain, “what is the Taiwan Presidential Hackathon and its challenge theme this year?”.

According to the Hackathon’s website:

“In line with the needs of the country’s social development, the Taiwan Presidential Hackathon, launched in 2018, is an initiative designed by the Taiwanese government to demonstrate its emphasis on open-source, open data, and related best practices to address the needs of the country through social innovations and economic development.

This event aims to facilitate exchanges among data owners, data scientists, and field experts to tap into the collective wisdom across government, industry, private and public sectors. Ultimately, it aims to accelerate the optimization of public services and stimulate inclusive social and economic growth for all people.”

The challenge theme of the 2019 international track of the Hackathon is to make a working platform which facilitates sustainable infrastructure development. Without further ado, our application is below. Enjoy!

2019 Taiwan Presidential Hackathon: Enabling Sustainable Infrastructure

Project Name: Enabling Sustainable Infrastructure The Madaster Platform for Material Identity

WHICH PROBLEM DO YOU WANT TO SOLVE:

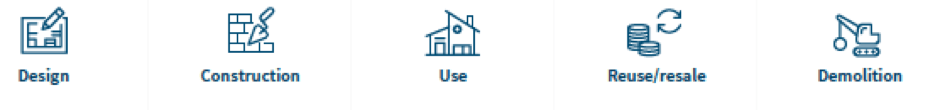

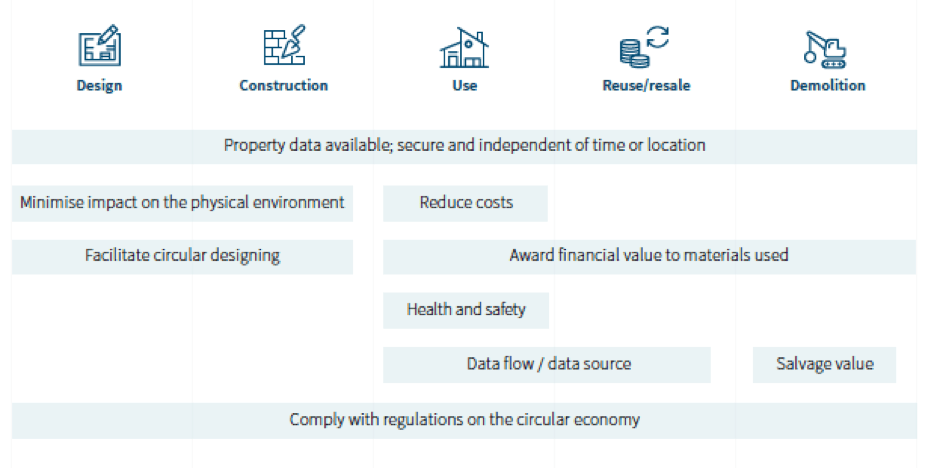

We want to solve the problem of waste. In our vision, waste is material without an identity. We can eliminate waste by giving materials and products applied in the construction sector an identity through detailed registration and documentation through material passports. Our focus is specifically upon addressing waste generated from buildings and infrastructure, a sector which globally produces 40% of all waste annually, in order to promote sustainable and circular materials management.

WHY IS THIS IMPORTANT:

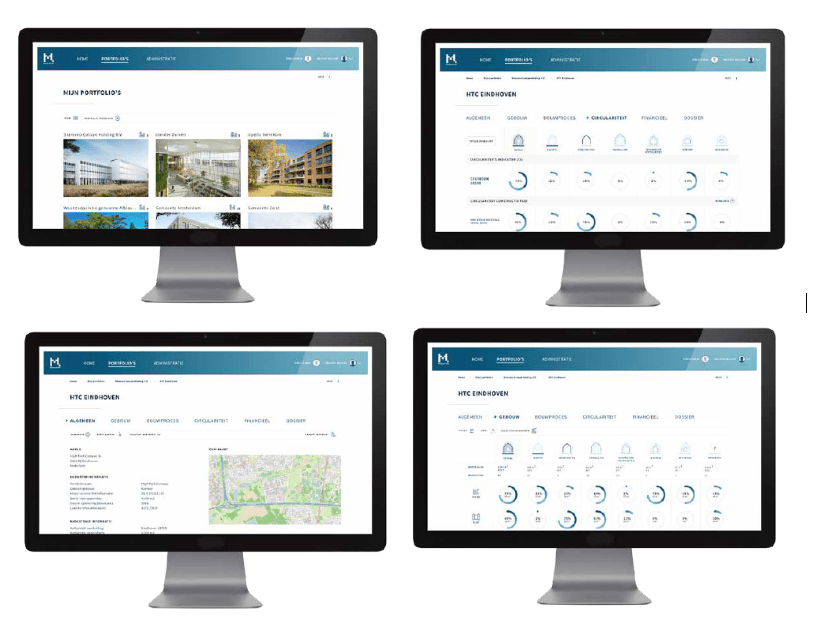

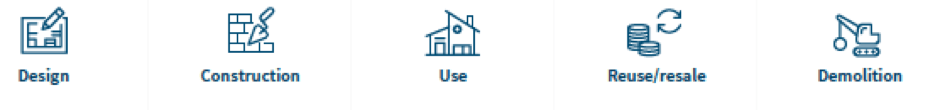

Our planet is a closed system, meaning that all our resources are limited editions. Still we throw away valuable resources – limited editions – as waste. And we don’t have to, as waste is material without an identity. With Madaster we want to give identities to materials applied in the built environment. Madaster created a register to safely capture all material and product data, within the limitations of privacy and security. Registration of materials contributes to the transition towards a circular economy, as the identity data of products and materials provide necessary insights in the potential reuse. The Madaster platform indicates to what extend circular characteristics are applied to a building and encourages circular design. Financial valuation of the materials in a building provide transparency in the potential financial benefit of reuse. With a register like Madaster, the potential of the material stock in real estate, infrastructure and regions can be identified and a transition towards a circular economy can be facilitated.

TO UNDERSTAND THIS PROBLEM WHAT DATA DO YOU HAVE:

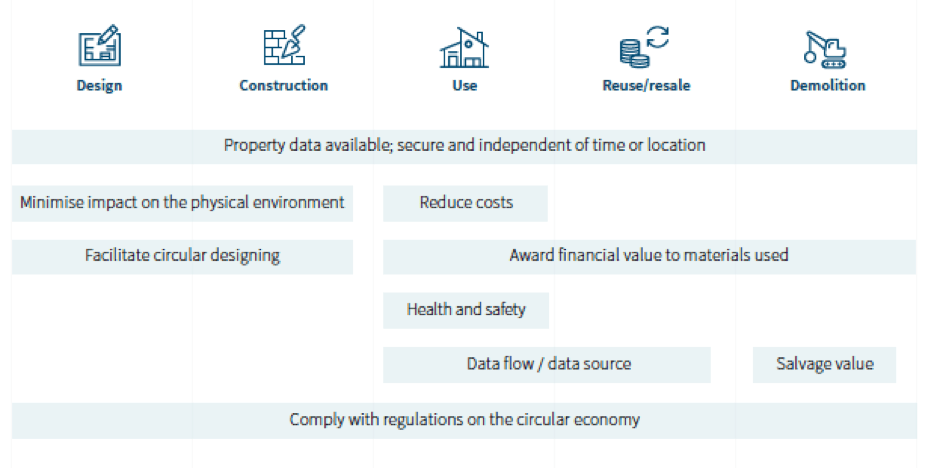

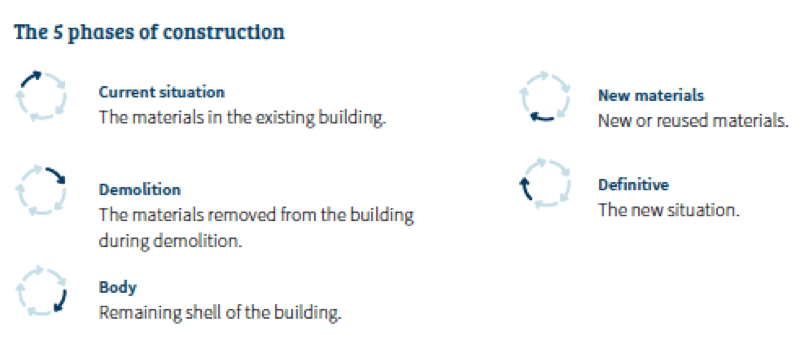

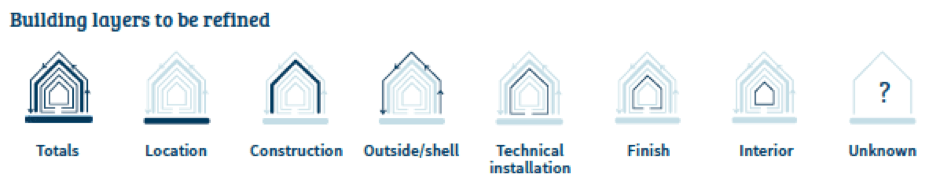

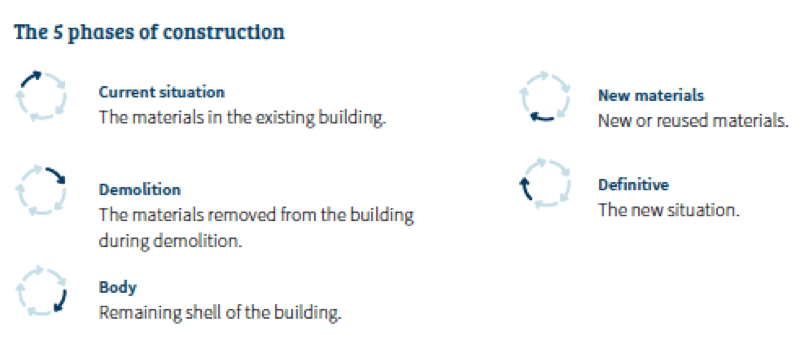

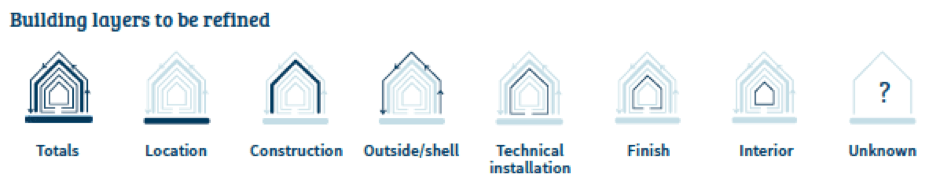

1st: Material related data: source files (BIM/IFC or Excel) are the basis of a building in Madaster. The building information models gives insight in the metrics (volumes) of materials and its characteristics. This is the basis for the material passport.

2nd: Pricing data: this data gives insight in the historical, actual and expected future value of materials. The transition towards a circular economy requires that we do not only give an identity but also a financial valuation to materials.

3rd: external product data sources for enrichment of the registration.

4th: building data, such as land registration details, images, quotations, assembly instructions etc.

5th: circularity data: to indicate the re-use potential

DO YOU NEED OTHER TYPE OF DATA? HOW DO YOU PLAN ON GATHERING IT?:

The platform is linked to external product data sources to enrich the registration and has an interface (API) for automated exchange of data with partners. Data Partners provide data and services that enrich the Madaster Platform and enhance data reliability. Examples of the data provided by Data Partners include financial, circular and material- and product-related data.

Globally we require additional data partners to enrich the platform the same way we did for the Dutch construction market. For Taiwan we need for example environmental data and price data in order to support the financial indicator and product data to enrich existing building registrations.

Because the working methods in Taiwan differ from those in the Netherlands, it is important to implement a local demonstration project. For Taiwan we have sought cooperation with Taiwan Construction and Research Institute (TCRI) to create a local proof of concept. We are convinced that if we can carry out a demonstration project locally we can convince Taiwanese businesses and the government of the added value of Madaster. This way potential customers, investors and data partners can be attracted.

PLEASE DESCRIBE THE EXPECTED OUTPUT OF YOUR PROJECT:

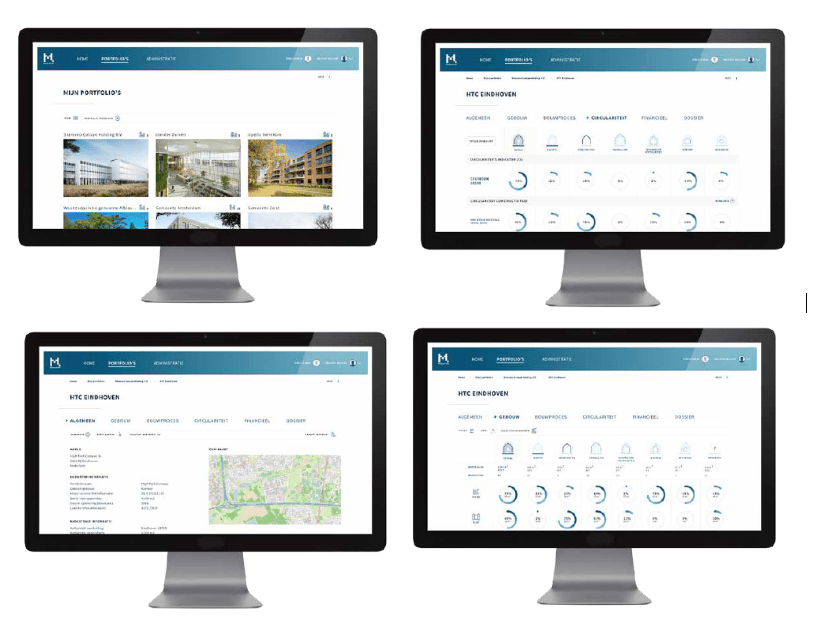

Globally we want to digitize all applied materials and products in the construction sector. Through documentation we can provide insight in the potential of existing material for reuse in a circular economy.

For Taiwan we want to demonstrate:

- The efficiency of applying existing information (BIM models) for registration in Madaster and the realization of the Madaster functionality (including materials passport, circular and financial valuation).

- The necessity of having detailed material and product data available for the realization of a circular economy and the way in which Madaster can realize this.

- The potential of a database with a public objective in which all products, materials and buildings are registered for the development and application of – new – circular business models such as market places, certification companies, financiers and builders.

WHAT IS YOUR PROGRESS TO DATE:

Madaster is a concept that has already been tested and proven to work. Since our launch in 2017 in The Netherlands we’ve registered over 2 million square meters in our database.

In 2018 we came in touch with two Taiwanese delegations from the construction sector. This introduction revealed the interest in the Madaster platform and the possibilities to facilitate the transition to a circular economy.

In November 2018 we visited Taiwan together with a Netherlands Circular Economy Mission to Taiwan. We visited the local governments of Taipei, Taoyuan, Tainan, Taichung, and the Taiwan Sugar Corporation (TaiSugar).

In March 2019 we signed an agreement to work together with TCRI as our local partner in Taiwan. This marks a unique opportunity to evolve and internationally expand Taiwan’s domestically-founded green building certification, EEWH, the world’s first green building certification designed for structures in sub-tropical regions. We also signed an agreement with TopOne International Consultants for a demonstration project of 167,772 m2. TaiSugar introduced their planned project for Yuemei Sugar Refinery (500m2) and another in Shalun (30,000m2). Furthermore, at this moment we are registering into our platform Taiwan’s first-ever circular building, the Holland Pavilion of TaiChung World Flora. All the materials and products of this building will be re-used by TaiSugar in future construction.

ONCE COMPLETED HOW DO YOU PLAN TO USE THE OUTPUT OF YOUR PROJECT:

Madaster has the ambition to realize a local ecosystem that consists of:

- a) a not-for-profit foundation that stimulates and oversees the transition towards a circular economy supported by the Madaster Platform and

- b) a Taiwanese service organization that develops and operates the Madaster Platform in Taiwan.

The outcome of the project and resulting platform will be used to kickstart the realization of the Taiwanese circular economy ecosystem.

DESCRIBE THE EXPECTED OUTCOME AND IMPACT OF YOUR PROJECT, ONCE IMPLEMENTED:

Globally and regionally we trust using the anonymized metadata of the platform is a way to help cities and governments better track and trace and understand their Resource Banks. Furthermore, this data can be used in conjunction with Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to analyze infrastructure and human settlements in a way which has never been done before. Specifically, this will allow for the analysis of the distribution and make-up of materials in human settlements which can in-turn provide profound data-driven indicators for the analysis of environmental and socioeconomic factors (i.e. inequality, environmental change, and sustainable communities). Importantly, this data can be used to understand the barriers to reaching the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and how to most effectively overcome them. The complete data set on the platform is supervised by the Madaster Foundation, a Dutch non-profit organization, in order to guarantee the privacy, security, and public availability of the (anonymized) data.

Madaster Taiwan will provide insights to construction owners, stakeholders, users and regulators in the potential of existing materials and products applied in the built environment. This potential can be monetized through reuse of materials and reduction of risks. Most of all, Madaster Taiwan will facilitate the elimination of waste through providing identities to all applied products and materials so they can never end up as anonymous waste.

ANY REFERENCES? LINK TO YOUTUBE OR CLOUD DRIVE?:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sh6yvOzlIZU

https://www.madaster.com/en or https://www.madaster.com/cn

https://mailchi.mp/8261d2d75d97/madaster-news-2019212

Grayson Shor

M.A. International Affairs, Specialized in Asia’s Emerging Circular Economy Ecosystem and Plastic Marine Debris

Sigur Center 2019 Asian Language Fellow

National Taiwan University, Taiwan

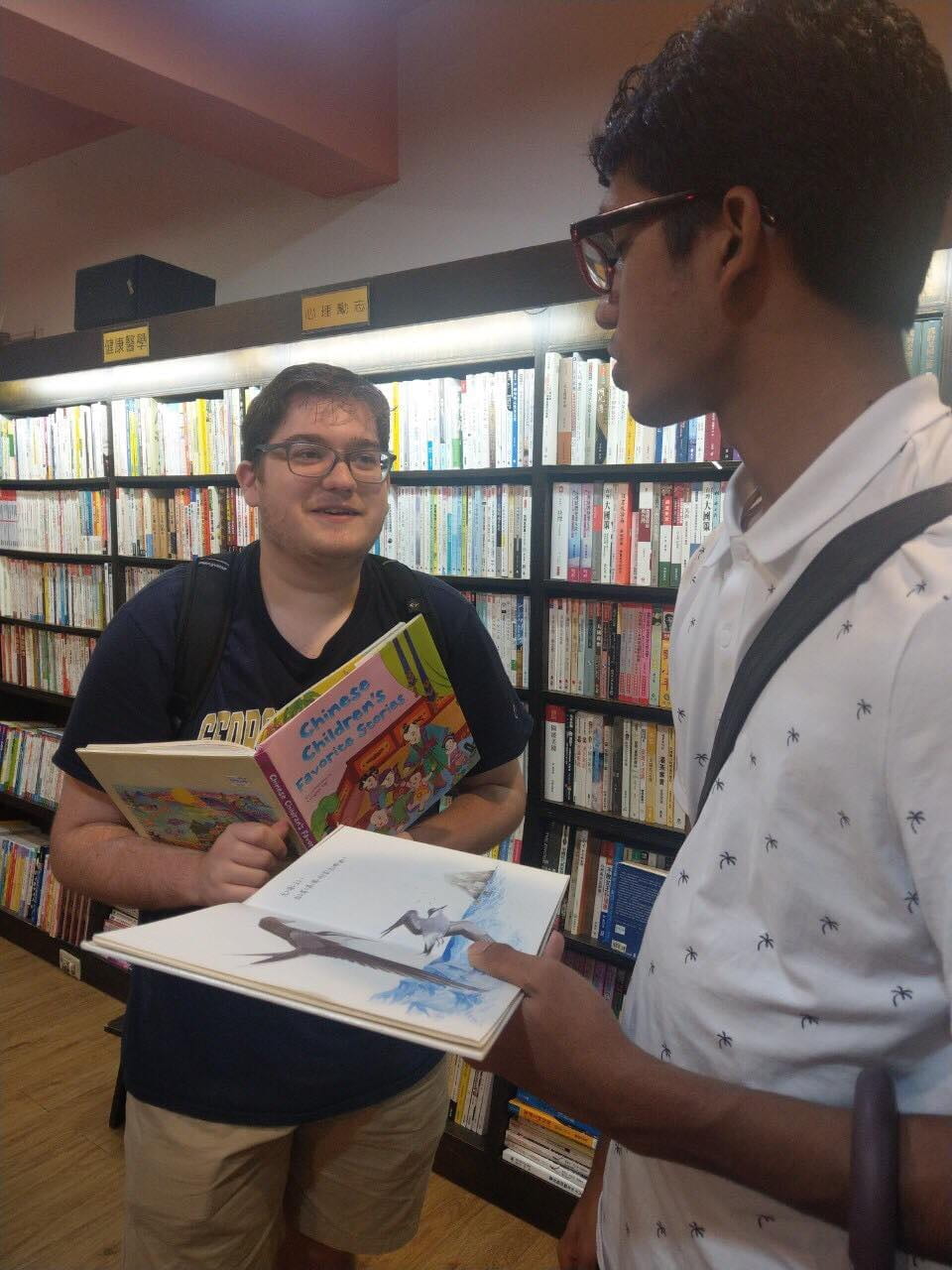

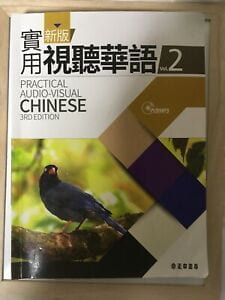

I was very lucky to meet a few Taiwanese locals who have helped me learn and practice more than I could learn in the classroom. I was able to work on fine-tuning my pronunciation, learn about Taiwanese culture, and much more. Through meeting language partners, I was also able to explore new parts of the city and try new foods every time I met up with a language partner – I’ve made some of my best friends in Taiwan this way. One language partner in particular even went to the extent of teaching me Zhuyin (also known as Bopomofo), which is the Taiwanese equivalent of Pinyin. It’s a feat in of itself as many Taiwanese people do not know how to use pinyin. Learning Bopomofo has helped to improve my pronunciation as well as allowing me to access more resources as children’s books often use Zhuyin. Language exchange allowed me to improve my speaking speed and learn more casual expressions that younger people will more often use. It has given me the liberty to design my own plans about what I wanted to learn and dive into topics that my classes may look over, such as movies or music that were trending in Taiwan. From talking about the work of Hebe Tien to Jay Chou, I discussed song lyrics and the clever ways that artists use Mandarin. I was also able to pick up on some Taiwanese (Taiyu) and Hakka words that have infiltrated into everyday Taiwanese Mandarin conversation to better appreciate the many regional variations of Mandarin. I learned about the many views on the upcoming presidential race and the controversial KMT candidates that have been stirring heated debate among the Taiwanese public.

I was very lucky to meet a few Taiwanese locals who have helped me learn and practice more than I could learn in the classroom. I was able to work on fine-tuning my pronunciation, learn about Taiwanese culture, and much more. Through meeting language partners, I was also able to explore new parts of the city and try new foods every time I met up with a language partner – I’ve made some of my best friends in Taiwan this way. One language partner in particular even went to the extent of teaching me Zhuyin (also known as Bopomofo), which is the Taiwanese equivalent of Pinyin. It’s a feat in of itself as many Taiwanese people do not know how to use pinyin. Learning Bopomofo has helped to improve my pronunciation as well as allowing me to access more resources as children’s books often use Zhuyin. Language exchange allowed me to improve my speaking speed and learn more casual expressions that younger people will more often use. It has given me the liberty to design my own plans about what I wanted to learn and dive into topics that my classes may look over, such as movies or music that were trending in Taiwan. From talking about the work of Hebe Tien to Jay Chou, I discussed song lyrics and the clever ways that artists use Mandarin. I was also able to pick up on some Taiwanese (Taiyu) and Hakka words that have infiltrated into everyday Taiwanese Mandarin conversation to better appreciate the many regional variations of Mandarin. I learned about the many views on the upcoming presidential race and the controversial KMT candidates that have been stirring heated debate among the Taiwanese public.