Transcript

Ben Hopkins:

Good evening everyone. Why don’t we go ahead and get to the goods, as it were. It is my distinct pleasure to welcome you this evening to what is the 24th annual Gaston Sigur Lecture, which celebrates and is done in memoriam of the life work and achievement of Gaston Sigur, who is also the namesake of the Sigur Center, which I am the director of.

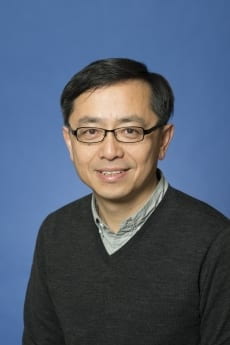

Ben Hopkins:

I’m Ben Hopkins, the Director of the Sigur Center, and it is my great pleasure this evening to welcome a distinguished guest and a very old friend, Professor Sunil Amrith from Harvard University.

Ben Hopkins:

Before we get to Sunil, it is my duty and pleasure to talk a little bit about our namesake, Gaston Sigur, give you some background on the Sigur Center, as well as Professor Sigur himself, who arrived here at George Washington University in 1972 to be the first head of what was then the Institute of Sino-Soviet Studies, and has subsequently transformed into being the Center that carries his name today.

Ben Hopkins:

Gaston Sigur was tapped by President Ronald Reagan in 1982 to be the Senior Director of Asian Affairs on the National Security Council, and in 1983 he was appointed as Special Assistant to the President on Asian Affairs. By 1986 he moved real estate down across the street to Foggy Bottom, being appointed and approved by the Senate as the Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs. He’s remembered for his strengthening of the American-Japanese alliance, as well as his push for democratization in Korea. He finished his illustrious career in public service in 1989, having carried through into the first Bush administration, and returned here to GWU, where he ended up retiring in 1992.

Ben Hopkins:

In light of his service, both to the University and the country, the elders of GW decided to name the newly established Center for East Asian Studies, which is today the Center for Asian Studies, after him: The Sigur Center.

Ben Hopkins:

Gaston Sigur passed away in 1995, and in memory of his longstanding works and contributions intellectually and to the policy world, we gather here today annually for our lecture, partly in his memory. His son Paul sends his regards; he could not attend this evening, and we do miss him, but we look forward to sharing this event through the website with him as soon as possible.

Ben Hopkins:

Now the Sigur Center today is the largest center for Asian Studies in the DC area. We focus no longer solely on East Asia, but as we can see from today’s topic, right the way across Asia, including South, Southeast Asia, and even venture as far afield as Central Asia.

Ben Hopkins:

I would also draw your attention to the back of the program, which announces, for those of you that have not heard, our success in recently winning a National Resource Center Title VI grant, which has designated us as one of 15 National Resource Centers in the country, joining Columbia, Harvard, and a few other universities you may have heard of. And as he’s here, it is also my pleasure to point out that much of the work for that was done by Ed McCord, who is going to be retiring next month.

Ben Hopkins:

So with that said, let me turn to the business of the day. As I mentioned, it is a distinct pleasure to welcome a distinguished academic. Very rarely is it that I actually get to say I stand in the presence of a genius. But as you can see from his featured speaker bio, Sunil won the MacArthur Fellowship, known as the Genius Award, in 2017, and a well-deserved win it was. I’ve known Sunil for a number of years; we were at Cambridge together. And apart from being an incredibly acute mind, he is also a very, very nice person, so it’s with that warmth that I also welcome him.

Ben Hopkins:

Sunil is currently the Mehra Family Professor of South Asian studies, and to my horror I just found out he’s the Chair of the South Asian Studies Department at Harvard; apparently even if you’re a genius, you get sentenced for your sins. And he is Director of the Joint Center for History and Economics [at Harvard].

Ben Hopkins:

Sunil has written a number of award-winning and truly groundbreaking books, the latest of which will, I think, form the basis of his talk this evening. His latest book, which he will address in his talk this evening, is Unruly Waters, which just recently came out with Basic Books and Penguin, is a history of the struggle to understand and control water in the South Asian subcontinent.

Ben Hopkins:

His previous extremely well received book, Crossing The Bay of Bengal, was published with Harvard University Press in 2013, and was recognized by the American Historical Association with the John F. Richards Prize for South Asian History in 2014. He also is the author of Migration and Diaspora in Modern Asia with Cambridge University Press in 2011. His first book, Decolonizing International Health: South and Southeast Asia, was published with Palgrave Macmillan in 2006, and in fact, that was the first time I remember hearing Sunil speak on Dr. Malaria, which was a long time ago, back in Cambridge.

Ben Hopkins:

Additionally, Sunil has authored a number of articles in the American Historical Review, Past & Present, and EPW. He’s on the editorial board at Modern Asian Studies, is a book editor for Cambridge University Press, as well as Princeton University Press.

Ben Hopkins:

Sunil arrived at Harvard in 2015, having served his time at Birkbeck, one of the University of London colleges, for nine years, and he has a longstanding connection as well, familial and professional, to Singapore, where he grew up.

Ben Hopkins:

With that, it is my great pleasure to cede the floor to a true genius, Sunil Amrith.

Sunil Amrith:

Thank you so much Ben, for a very, very kind introduction, which I will struggle to live up to. But it’s very, very nice, it’s a particular honor to be here on the invitation of Professor Hopkins, whom I’ve known for—I don’t want to count how many years, but close to 20, I think. It’s an honor to be here giving the Sigur Memorial Lecture. Thank you all for being here at a busy time at the end of the semester.

Sunil Amrith:

My subject today is “Water and the Making of Modern India,” and I’d like to begin with a well-worn cliche. In 1909, the finance minister in the British Imperial government of India declared that, “Every budget is a gamble on the rains.” That phrase has been repeated countless times since then. It still appears in Indian newspaper reports every year.

Sunil Amrith:

Half a century later, the sentiment held. “For us in India, scarcity is only a missed monsoon away,” Prime Minister Indira Gandhi said in the late 1960s. And then just last year, in a lecture that she presented at Harvard, one of India’s best known environmentalists, Sunita Narain, declared in an off-the-cuff remark, “India’s Finance Minister is the monsoon.”

Sunil Amrith:

At ground level, this is to simply state a basic truth. Even today, close to 60% of India’s agriculture is rain-fed, subject to a monsoon climate that has always been intensely seasonal, and subject to a good deal of internal variability. But the story I want to tell this evening is not one of climate as destiny. Rather, it’s a story of how the idea of climate as destiny has had significant political implications in modern India.

Sunil Amrith:

When I mentioned recently to somebody that I was working on the history of the monsoon, they asked, “Does the monsoon need a history? What sort of history?”

Sunil Amrith:

For a start, the monsoon has a natural history, and we can see this in Pranay Lal’s wonderful book, Indica: A Deep Natural History of the Indian Subcontinent. And in that, Lal sketches a story of a monsoon that has evolved over tens of millions of years, leaving an archive of its natural history on the seabed and on land. Traces embedded in tree rings tell us that the Asian summer monsoon has strengthened during warm inter-glacial periods, and weakened during periods of planetary cooling, as during the so-called Little Ice Age that lasted through the middle of the 16th to the early 18th centuries.

Sunil Amrith:

Since the late 19th century, meteorologists in India have pioneered the study of the periodicity of the monsoon’s internal variability, leading to the discovery of how the monsoon is tele-connected, as they say, with other parts of the planet’s climate, including especially through the El Nino-Southern Oscillation.

Sunil Amrith:

But the monsoon also has a modern history, a human history, which is what I will be concerned with this evening. The monsoon has shaped, and continues to shape patterns of economic life in India, but one of the most fundamental shifts over the past half century is really the coming together of the monsoon’s natural and human histories, reflected in mounting evidence that human activity is itself reshaping the monsoon.

Sunil Amrith:

It has a human history in the sense that this is also a history of science, a history of climate science in India. It has a history in the sense that it is part of a history of ideas about climate, nature, and society. And I shall suggest this evening that water has been central to different conceptions of India’s freedom and India’s future.

Sunil Amrith:

The monsoon has long evoked many emotions: Anxiety, longing, wistfulness. This is a very well known photograph of Raghubir Singh, which hangs in MoMA: Monsoon Rains, Munger, Bihar. I’ll focus on the prosaic in my lecture today, but I think we also need histories of the monsoon in Indian art, literature, music, photography.

Sunil Amrith:

I’d like to begin with a moment where, really for the first time, it seemed that the monsoon might just be a problem that could be solved. Reflecting on the state of India’s development, the members of the Indian Industrial Commission wrote confidently in 1918, that: “The terrible calamities, which from time to time depopulated wide stretches of the country, need no longer be feared. In a monsoon climate,” they said, “failure of the rains must always mean privation and hardship, but no longer need it lead to wholesale starvation and loss of life.”

Sunil Amrith:

This conveyed a strong sense that something fundamental had changed in India over the first two decades of the 20th century. The risk posed by climate had been mitigated, both by policy, by the early warning system of the famine codes, and by technology; above all, by irrigation. As long as India remained predominantly agrarian, some level of risk would remain, but the Commissioners envisaged a future in which industrialization would provide new employment and greater security as India’s population moved from the countryside to the cities.

Sunil Amrith:

In the 1870s, the idea that famine was inevitable in India prevailed amongst British administrators. By the 1920s, most observers believed that India had conquered famine, and yet the worry about water did not go away. We can see this deep anxiety about the material underpinnings of life in the ways that many leaders in Indian politics, leaders in the nationalist movement, scientists, engineers, thinkers wrote about freedom, because in many of these conceptions of freedom, water was crucial.

Sunil Amrith:

“Modern science claims to have curbed the tyranny and the vagaries of nature,” Jawaharlal Nehru wrote in 1929, but there remained a large gap between that potential and the reality of life for millions of Indians. Nehru, amongst others, was clear about the material urgency behind every vision of freedom. “Our desire for freedom is more a thing of the mind than the body,” Nehru said. He was talking to his colleagues. “But for most Indians,” he said, “they suffer hunger and deepest poverty, an empty stomach, and a bare back.” “For most of India’s population,” he said, “freedom was not the thing of the mind, but a vital bodily necessity.”

Sunil Amrith:

For his part, Mahatma Gandhi made a different sort of link between nature and freedom. We see this during his iconic Salt March. Choosing the British Salt Tax as the symbolic focus of his nonviolent protest, Gandhi observed that next to air and water, salt is perhaps the greatest necessity of life. The vital properties of salt linked the coastal ecosystem with the lives of millions inland. Gandhi’s was an argument about climate and society. He pointed out that the poorest who labored outdoors in the heat, were those most in need of salt and sustenance.

Sunil Amrith:

So a wide range of Indian thinkers, scientists, activists, drew different lessons from their awareness of this pressing material need, and the centrality of water to that need.

Sunil Amrith:

We can see this, for example, in the divergence of opinion between the sociologist, Radhakamal Mukerjee, and the scientist, the astrophysicist, Meghnad Saha. Both of them were concerned with Bengal’s rivers. Both of them recognized the centrality of water to the livelihood of people, to agriculture, to health. And both of them saw the importance of water to India’s future, but they saw that future very differently.

Sunil Amrith:

Mukerjee believed that a restoration of what he called writing in the 1920s and thirties “ecological balance and respect for the distinctive nature of each riverine ecosystem” would provide the seeds for revival.

Sunil Amrith:

Saha’s prescription could not have been more different. Saha was scathing in response to those like Mukherjee, who’d argued that afforestation and local efforts of soil conservation would strip the Damodar river, for example, of its destructive power. He called the claim – which was widely believed in the 19th century – that deforestation affected rainfall, absurd. Saha wrote that this was a claim for which there was not a single iota of positive proof. If changes in forest cover and land use had any effect on local climate, Saha argued, these must be extremely small compared to the huge monsoon currents, which are responsible for India’s rainfall. So rainfall, in Saha’s imagination, was beyond human intervention.

Sunil Amrith:

But human intervention to transform the landscape could neutralize the threat posed by hydraulic uncertainty, securing rivers from the alternating paucity and excess of water. And here Saha was confident about the future. “We are fortunate,” he wrote, “to live in a time where the large-scale experience of thousands of dams constructed in the United States are at our disposal.” He believed that the global circulation of ideas and technology, a process of learning would come to India’s aid.

Sunil Amrith:

In valorizing the Tennessee Valley Authority, and also the Soviet example, Saha indicated that his dreams for India extended beyond anything that the sluggish British colonial stage could carry out. He envisaged the construction of dams in eastern India that would last for hundreds of years.

Sunil Amrith:

My invocation of Saha brings us to the topic that, I think more than any other, has dominated discussion of India’s water policy, and that is large dams. As I’ll discuss in a moment, large dams have undoubtedly been of pivotal importance symbolically, socially, ecologically, but I think it’s also a mistake to search the early 20th century only for the roots of India’s later enthusiasm for large dams. Instead, what we see, I think, is a multiplicity of ways of addressing India’s dependence on the monsoon, and these were at once more vocal and more global than the exclusive focus on large dams as a matter of national policy would suggest.

Sunil Amrith:

In 1951, India carried out its first census after independence. It was, at that time, the largest census ever undertaken in the world. The average life expectancy in India stood at just 31 years for men and 30 years for women. Already in the US, at that time, that figure was 65 years for men, and 71 for women. For every thousand live births in India at the time, more than 140 infants died. And in the minds of many of India’s leaders, this was an indictment of two centuries of British rule.

Sunil Amrith:

The political theorist, Pratap Mehta, has argued that the immediate converts of political power in post-colonial India was dictated by the intensity of mere life. That is to say, poverty and destitution put most Indians – and Mehta in this sense echoes the quotation from Nehru that I gave out just a few minutes earlier – under the pressing dictates of their bodies, and the imperative to address these needs, Mehta observed, can have no limiting balance. “This simple logic,” quoting Mehta, “transports power from a traditional concern with freedom to a concern with life and its necessities.” In this quest, the conquest of nature was pivotal.

Sunil Amrith:

The 1950s were characterized by a newfound ambition and confidence that the dictates of nature might be conquered. There’s no question that large dams, perhaps more than any other technology, came to symbolize progress and freedom in post-independence India. It was an era when, in Sunil Khilnani’s memorable phrase, “India fell in love with concrete.” Excellent visual illustration of the allure of large dams that was mounted an exhibition held at the Nehru Memorial Museum a few years ago, called Dams in the Nation. And a lot of this was really about the symbolic power of dams as symbols of freedom and independence in newly post-independence India.

Sunil Amrith:

This is a picture of Nehru at the ceremonial inauguration of the Bhakra Dam in Punjab, addressing a crowd of hundreds of thousands of people. This is taken from one of dozens of public information films which played before the feature blockbusters in the cinemas of the 1950s, telling a heroic story of India’s war against nature.

Sunil Amrith:

Nehru’s reflection that these dams were the temples of new India has often been cited. Kanwar Sain, the second head of India’s Water Authority, wrote that, “These river valley projects constitute the biggest single effort since independence to meet the material wants of the people, for full irrigation brings ultimately, the sinews of the man from power to sinews of industry. And these were multipurpose projects designed simultaneously to provide irrigation, water, and hydropower. Cruel reality: More than 90% of the dams of India have been used primarily for irrigation.

Sunil Amrith:

Sain voiced the hopes of many of India’s planners and architects when he declared that dams are indeed the symbols of the aspirations of new India, and the blessings – note this shift to a religious language – that stream forth from them are the enduring gifts of our generation to posterity. Note the fusion of the language of science and faith, reason and eco-rapture.

Sunil Amrith:

So one aspect of the story has been very well studied, and that’s the very tangible influence of American hydraulic engineers, people like David […]. On the Damodar Valley Corporation in particular, Dan Klingensmith wrote an excellent book on this. And my friend David Engerman’s exhaustive recent history of India in the Cold War adds a lot of detail to that. But the point I’d like to make here is that the Americans and the Soviets were not the only influences on India’s love affair with dams. India in turn shaped approaches to the challenge of water across Southeast Asia.

Sunil Amrith:

So in May 1954, Kanwar Sain – who I just quoted – chairman of India’s Water Commission, and KL Rao embarked on an official visit to China. Their goal was to report back on China’s water projects in the first years of the People’s Republic. They focused in particular on Chinese attempts to use dams to control flooding along the Yangtze and other rivers.

Sunil Amrith:

Sain and Rao were in fact amongst the first outsiders to see firsthand China’s massive hydraulic experiment. They arrived in China in May 1954, and they stayed for two months. They spent much of their time on the water. They actually traveled by boat along the Yangtze for most of their journey. They were the protagonists of India’s colossal efforts to control water, and yet the scale of work that they saw in China dazzled them. They undertook their tour of China exactly half a century after the Indian irrigation Commission had traveled through India in search of water. And in a sense, theirs was part of the same quest. The farmers of the late 19th century had unleashed in India a desperate and continuing search for sources of water to mitigate the dependence on the monsoon.

Sunil Amrith:

Sain and Rao were both trained squarely within a colonial tradition of Indian water engineering, but now they represented an independent nation, and for inspiration they looked not only to Europe, to America, but to revolutionary China.

Sunil Amrith:

And consider the contrast between the two tours. When the Indian irrigation Commission, at the beginning of the 20th century, traveled with a retinue of servants and specially chartered trains, Sain and Rao were given strictly limited foreign exchange and accompanied by just two interpreters.

Sunil Amrith:

Their report contains an extended list of every single Chinese official they met, from ministers to field engineers to water scientists at the College of Hydraulic Engineering. They were struck by the quality of China’s hydraulic engineering. They delighted in the firm emphasis given to technical education in China. They praised the Chinese capacity for improvisation, building huge dams from local materials when imports were in short supply. Naturally, their thoughts turned to comparisons with India.

Sunil Amrith:

There were clear differences in the challenges that each country faced. One sharp contrast between India and China was indeed climatic. Once again, what made India distinctive was the monsoon. “Unlike India, hemmed in by the Himalayas,” they wrote, “China is open to Central Asia. This meant that in the summer, China, unlike India, is not the single objective of the air circulation of a whole ocean.”

Sunil Amrith:

By contrast, China’s rivers were more menacing than India’s, more prone to burst their banks. So in Sain and Rao’s stark comparison, India’s great need was irrigation, China’s was flood control. Both our countries bide an industrial future. Of course, the promise of hydroelectric power attracted them both.

Sunil Amrith:

Sain and Rao returned to India with a firm sense that there were lessons that India should learn from China. But there were ominous portents, too. In his farewell speech bidding Sain and Rao farewell, the Chinese Director of Water Resources had described how China’s water projects had been extended to the border regions of our fraternal minorities to promote national unity. There was no attempt on the Chinese side to disguise the fact that water was intrinsic to political power. The conquest of water meant the conquest of space. Unspoken at the time was the sense that some day the border regions in question may include China’s borders with India.

Sunil Amrith:

Sain and Rao faced another problem when they returned with the first ever maps of China’s water projects to be seen outside China. The Indian Ministry of External Affairs was rankled by what Sain and Rao had missed; that the maps they’d been given by Chinese water officials claimed as Chinese territory a large part of the borderland that the Indian state saw as integral to India. The maps were destroyed.

Sunil Amrith:

Interestingly enough, in the Indian edition of my book, Unruly Waters, the maps were deleted at the very last minute, before it was published. These are still very, very sensitive issues, particularly the maps illustrating that chapter on India and China in the 1950s. The maps were destroyed, redrawn to accord with India’s understanding of its territorial boundaries.

Sunil Amrith:

Sain later wrote in his memoirs that he was deeply grateful this had been done before the volume was published. If it had not, it would have been a source of great embarrassment a few years later, when India and China went to war over just those borders. Tellingly, Sain and Rao’s report was, after 1962, treated as a classified document until the 21st century.

Sunil Amrith:

Just as China’s experiences inspired India’s water engineers, so India became a model to the rest of Southeast Asia. In 1955, the director of the UN Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East, the South Indian economist […], commissioned Kanwar Sen to join the UN mission to survey the Mekong river. “The prick has gone too deep to be halted.” That’s how Sen described his sense that large scale hydraulic engineering was inevitable now in the Mekong as elsewhere in Asia, given the bold claims that had been made on behalf of big dams, given the hunger for progress and development that he saw wherever in the world he went.

Sunil Amrith:

The Mekong commission was quickly overshadowed by the escalation of American involvement in Indochina as the US became caught up in military conflict in Vietnam, then engulfed Vietnam’s neighbors as well. But Sen actually continued in his job. He was a patriotic Indian engineer at the pinnacle of his profession, enamored of China, but with close personal and professional links to the US Bureau of Reclamation. He chose to spend a decade of his career with what became the Mekong River Commission, trying to coordinate the development of Asia’s most international river, notwithstanding the palace politics that the scheme was stymied by.

Sunil Amrith:

In his memoir, Sen hints the material reward of working with the UN might have been one incentive for him to stay, but his motivations went much deeper than that. He believed, like so many of his generation, that taming the waters was a goal beyond ideology. Working for the UN alongside many former colonial civil servants, engineers now turned to development consultants, Sen held a vision of Asian nations working together to claim their rightful place in the community of nations.

Sunil Amrith:

In a memoir that is detached, even clinical in tone, a rare moment of emotion comes when Sen describes what he says was his pilgrimage to the site of Angkor Wat in Cambodia while on his first Mekong mission. “I was very much moved by the ancient glory and culture of India reflected in Angkor Wat,” he wrote. Just as many of India’s water engineers at home presented their new temples as really standing within an ancient historical tradition of Indian water engineering, so here Sen appealed to a deep history of cultural exchange across borders to provide ballast for his vision of an Asia united by the challenge of water.

Sunil Amrith:

By the mid 1960s, this approach to water that had epitomized the post-independence period ran into trouble. In 1965 and ’66, large parts of India suffered from drought. This threatened food shortages, even led to famine being declared in Bihar, the first since Indian independence. India’s growing and uncomfortable dependence on American food aid was clearly illustrated by the monsoon fairies of the 1960s. “How helplessly we are at the mercy of the elements,” a newspaper editorial lamented in 1965, arguing that really all India had to show for the previous decade of development efforts were some shallow and tentative improvements in irrigation.

Sunil Amrith:

The crux of the Indian government strategy from the mid 1960s onwards was to concentrate modern inputs in irrigated areas. This is a very prosaic way to describe a fundamental change. From the 19th century India’s geography of water had shaped plans for the country’s future. Now the difference between irrigated and rain fed lands would be accepted as a necessary inequality even as a matter of strategy. It drove what we know as the green revolution, which combined the substantive irrigation inputs with new high yielding seeds that had first been tried in Mexico and the Philippines. The precondition for the growth of the green revolution in India was a massive expansion in irrigation, and however large the downs, however monumental, they were insufficient.

Sunil Amrith:

Cultivators in arid parts of India have known for centuries, and the British recognized the 19th century that India’s groundwater resources provided perhaps a better insurance against drought. As early as the 1880s British authorities in Bombay and Madras had experimented with electric pumps to extract groundwater. In 1950, there were already around 150,000 electric pumps in use in India. By the end of the century that number was 20 million, and India was the largest user of groundwater in the world. Until the 1960s groundwater could not be mobilized on a large enough scale to meet India’s requirements. The widespread use of tube wells and electric pumps changed that decisively. And if you look at this graph of irrigated India, you see a very sharp increase around the end of the 1960s. All of that is groundwater.

Sunil Amrith:

As a lawyer for the […] show, India’s groundwater law, however, continues to be shaped by colonial precedence that accorded absolute rights over groundwater to property owners, with no recognition of its growing public importance for Indian agriculture. I’ll talk about some of the consequences of this in the last part of my talk. Large dams had held out the promise of irrigation water plus hydroelectric power. In the groundwater era, demands for water and energy came together in a different way. State governments encouraged the pursuit of productivity by subsidizing the capital costs of infrastructure for this intensive exploitation of groundwater.

Sunil Amrith:

State electricity boards reduced the cost of electricity. By the 1970s, unable to bear the cost of monitoring energy use by millions of farmers dispersed across the country, state electricity boards opted for flat tariffs. As a result, agriculture’s share of total energy use in India grew from 10% in 1970 to 30% by 1995, even as the state electricity boards accumulated huge losses. Groundwater today accounts for 60% of India’s irrigated area, surface irrigation. The large dams only 30%. All the while, and despite the declining importance of surface irrigation, the profusion of large dams continued.

Sunil Amrith:

In fact, the 1970s were the peak decade of dam construction in India, and the social and ecological costs have multiplied. Since the 1950s, large dams have displaced millions of people in India compounding the loss of land and livelihood with the rupture of communities through the process of resettlement. The range of estimates for the number of people displaced specifically by dam projects in India ranges from 16 to 40 million people since 1947. These estimates come from the World Commission on Dams. The Red Cross, in 2012, went for the higher end of that range, as has the work of activists like Warren Fernandez and the geographer Sanjay Chakraborty.

Sunil Amrith:

So between 16 and 40 million people displaced by large dams. Under classes have been by far the worst affected, least able to negotiate adequate compensation from state and local governments. The environmental consequences of large dams have also been concentrated in the areas of the dam’s construction. Reservoirs have drowned millions of hectares of forest. Canals and barrels have disruptive water flow and drainage, often accompanied by a rise in vegetable diseases.

Sunil Amrith:

There was nothing inevitable about this outcome. I think we should not lose sight of the ambivalence and complexity with which these questions were viewed, even as these policies were being enacted. Even as large projects were pushed forward heedless to protests, this was accompanied by a growing consciousness of sustainability and loss, and the rise in India of one of the world’s most diverse and large environmental movements. It’s the first UN conference on the environment, as many of you know, it was held in 1972 in Stockholm. And Indira Gandhi was actually one of the very few heads of state to attend that first conference on the environment.

Sunil Amrith:

And in her speech to the plenary session she discussed the ecological problems that were already a matter of public discussion in India. She set out a position that saw environmental degradation is primarily a problem of poverty, a problem of distribution, not of numbness. She reminded her audience that we inhabit a divided world, and I think rightly many scholars have drawn a straight line from Indira Gandhi’s speech to the sorts of positions that the Indian government took right through the nineties and two thousands in climate negotiations. Indira Gandhi attributed historical responsibility for environmental destruction to the wealthy countries of the world. Many of the advanced countries of today reached their present affluence by their domination of other races and countries, she said, and through the exploitation of natural resources.

Sunil Amrith:

“We do you not wish to impoverish the environment any further,” she insisted, and yet we cannot for a moment forget the grim poverty of large numbers of people. Her most resonate phrase, the one for which the speech is usually quoted, was in the form of a question. “Are not poverty and need the greatest polluters?” She concluded by describing to her audience how she saw India’s quest since independence. “For the last quarter of a century,” she said, “we’ve been engaged in an enterprise unparalleled in human history. The provision of basic needs to one sixth of mankind within the span of one or two generations.”

Sunil Amrith:

It is such a startlingly simple insight, but one that we’ve perhaps forgotten in this application of speed, urgency, and scale by her recognition of the demographic and material transformations that were sweeping the world in the 1970s. She was pointing to a phrase that subsequent environmental historians have really labeled the great acceleration. As I mentioned a minute ago, the 1970s were also the moment that India saw the rise of a diverse but interlinked set of environmental activists. These included rural movements like the famous Chipko movement as well as urban activism. A group in Bombay in the 1960s and 70s, for example, called so clean, which took an early interest in air and water pollution.

Sunil Amrith:

Since the 1970s the wave of local opposition to large dams, in particular, has grown into one of the largest social and political mobilizations that India has seeds since independence. The best known of them is the non mother movement, but there are many others alongside it. The first citizens report on the state of the Indian environment, which was published in 1982, was something of a landmark intellectually in the development of India’s environmental movement, and articulated this very specific connection between social justice and environmental protection, which I think has characterized environmentalism in India. Interestingly for me as a historian, many environmental activists in India in the 1980s began to look to the past.

Sunil Amrith:

They began to look to what we can probably conclude is a romanticized idea of a past of harmony and ecological balance. This is a very influential publication from the mid-1980s, “Ding wisdom, the rise fall and potential of India’s traditional water harvesting systems.” They drew on a tradition of thought that went back to rather common Mukherjee and Gandhi. They sought the principles of ecological balance and traditional practices of farming, fishing, and artisanal production.

Sunil Amrith:

Their edition of the past was in many ways a useful fiction. It doesn’t really accord with what environmental historians and archaeologists have shown us about the environmental history of South Asia over many centuries. But nevertheless, this particular vision of a past of ecological balance was mobilized in a very powerful way politically. So let me come to a conclusion. I suggested at the beginning that from the beginning of the 20th century, the monsoon has been seen as a fundamental problem in modern India. Geological research has shown that the monsoon over the last twenty, thirty years has exhibited increasingly erratic behavior.

Sunil Amrith:

Regional drivers of changes in the monsoon circulation, chiefly driven by aerosol emissions and land use change interacts with planetary warming to make the monsoon increasingly erratic, increasingly prone to extremes. The monsoon does less well than almost any other climatic phenomenon in global climate models because it is so complex. As ever, most attention has been given to solutions that are squarely in the tradition of top down water engineering. For example, a river linking project, which is underway now in India with the strong support of the current government to build tens of thousands of kilometers of canals to link India’s Himalayan rivers right down to the Southern tip of the peninsula.

Sunil Amrith:

Interestingly enough, the architects of the river linking project quite explicitly see their inspiration as the 19th century British water engineer, Arthur Cotton. In constant, we’d see that Arthur Cotton in the 1870s wrote about: “Wouldn’t it be great if we could bring the Himalayan rivers down to the tip of the peninsula?” It embodies a view that the civil servant Ramaswami Iyer, who was a big proponent of large dams, but towards the end of his life changed his mind, decried just a few years before he died, as reflecting a Promethean attitude to the control of water. The space of dam building in the Himalayas in particular has met with resistance, and it comes with heightened risks. And this is a map from a few years ago of all the proposed dam sites in the Himalayas. And this was from the geological mapping that on top of the most seismically active zones in the Himalayas.

Sunil Amrith:

The risks are ecological, the risks are geopolitical, given that each one of these rivers is transnational and crosses boundaries in a part of Asia where there are very few treaties governing water sharing. Meanwhile, groundwater levels in parts of Northwestern and South Eastern India are particularly depleted, and this is a NASA satellite image that shows the shift just from 2002 to 2008 in ground water levels in India’s agriculturally most productive region. I am neither a water policy expert nor an engineer. I am concerned with what the perspective of history can bring to illuminating some of our public debates about water and climate.

Sunil Amrith:

So a few words and conclusion on what I think a historical perspective can bring. Living with the uncertainty of the monsoon has been an inherent part of life in South Asia from the earliest times. Over centuries, South Asian societies have evolved complex social and economic institutions, including, not limited to sophisticated irrigation systems to mitigate the fundamental problem of uneven rainfall and variable river flow. Between the mid 19th and the mid 20th century, the management of India’s water resources changed scale, underpinned by confidence and technology’s capacity to channel, even maybe to conquer nature. The intellectual and infrastructural legacies of that era epitomized by a belief and an investment in massive hydraulic engineering still shape water policy in South Asia. As the legal scholar Jed Perdy has argued in a wonderful book called After Nature, the material world that we inhabit is in many ways a memorial to a long running legacy of contested ideas about nature.

Sunil Amrith:

And in just this way, the current landscape of water in modern India is an outcome of a legacy of contested ideas. Colonial responses to an unfamiliar and unpredictable climate, in the context of agricultural capitalism, nationalist ideas about securing India from famine and deprivation, provisions of scientists and engineers who imagined new ways to harness water, and not least, the claims of hundreds of millions of Indian voters who demanded for their communities and their regions the fruits of progress and development. It is also an outcome of vast inequalities.

Sunil Amrith:

Inequalities in access to land, to water, and to energy. Inequalities in different groups’ ability to participate in the decisions that govern their lives and livelihoods. So we contend today with the consequences both of success and of failure in that endeavor. And by extension with the successes and failures of Indian democracy, in what Indira Gandhi called its unparalleled effort to provide for the basic needs of one sixth of mankind within the span of one or two generations. The scale of the water crisis facing India today is sobering. But the most important lesson that I think a historical perspective holds is that water management never has been and never can be a purely technical or scientific question. Ideas about the distribution and management of water in India are deeply inflected with cultural values, with notions of justice, with hopes and fears of nature.

Sunil Amrith:

Thank you very much.

Ben Hopkins:

I think Sunil just – I think Sunil just demonstrated why we won a 2017 corporate prize. Thank you for a very thought-provoking talk, Sunil, and I’m sure there’s many questions for all of you’s fine privilege, just briefly.

Ben Hopkins:

But I’ve got one question for you, and that is very clearly sketched out a tradition of technocratic modernism for water management in India the water dam maintenance, economic development. But then my attention was drawn in particular to your picture of the overlay of seismic zones and dams. And actually, Dan Hanes a while ago gave a little presentation that had something similar, and that drew my attention to that map was also a map of security issues for South Asia, right?

Ben Hopkins:

You mentioned, of course, that Adivasi threshold being disproportionately affected by displacement, which makes me wonder how does that feed into state insecurity domestically, along frontiers and the borders. Then even talking about geopolitics – who’s going to control the […] for the Indus that the part of governing water isn’t intimately linked with the art of governing the hills.

Ben Hopkins:

And, so I wonder if you might comment on a third area you hinted at in your talk, and that is perhaps, the security, securitization of the water.

Sunil Amrith:

That’s a vastly important dimension of this. One thing that strikes me is really how relating 20th century the hills came to be the focus of this water engineer. And I’ll get into that specifically, precisely as you asked, that it’s only as both Beijing and Delhi have sought to position themselves in this frontier area that this infrastructure is part, and that part of that establishing presence in the stage.

Sunil Amrith:

Road building usually precedes dam building, almost every one of these cases. I think you have many ways Chinese instance of the post-1980s liberation dams, perhaps even a better example than the Indian one I have given today of how close the security, governability, governance and water management are.

Sunil Amrith:

So then we turn the question that the frontiers of water engineering in this entire India are also regions which central governance have the disingenuous hold over, which are regions where local populations are being disenfranchised. Often feel alienated from exactly those kinds of nation-building, modernizing projects from the 20th century on, providing and aligning logical moves […].

Ben Hopkins:

Now, let’s open it to the floor. My questions, my only request would be if you could identify yourself before you ask your question. Yes?

Speaker 3:

Hello. Hi. My name is […]. I am a senior and double majoring in history and international affairs. My question is sort of related to the question that Dr. Hopkins asked. The rationale is that dams in India are a symbol of progress and modernity, and also the indigenous peoples and central tribes seem to be disproportionately affected by these.

Speaker 3:

I was wondering if you thought there was some sort of connection between the fact that internal development for roads in India conceptualize […] backwards populations? And […] progress, as related to the fact that there are the people who are most easily displaced in this vulnerable are you find, because of these symbols of progress.

Sunil Amrith:

I think you put more eloquently than I did, and that’s because it is exactly one of the reasons why they have been disproportionately affected is because their state’s view of themselves to progress is something that’s rooted. […] doesn’t change very much after Indian independence. So if in a sense, there are many scholars and then Adivasi activists who almost write some new channel for those and these are often I think some of the terms of the state’s approaches to those communities.

Sunil Amrith:

So there’s that, but there’s also the fact that of course, the Adivasis’ lifestyles and livelihoods depend on forests. And it those forests that are both economically valuable, but also precisely where these dams are to be built, make way for a different kind of primitive landscape and for a different kind of infrastructure. But I think that […] is important.

Sunil Amrith:

We know people are asking the question, but why are they not heard? Why does it take until the 1970s, 1980s for there to be large-scale protests against these types of displacements? But I think a lot of that has to do, also it has to do with more so that has to do with inequalities of power, and it has to do with precisely that. I think Mary says in the late 1940s the very first group people who are displaced in India was for the […]. “If you want to suffer, at least you suffered for the issues.”

Sunil Amrith:

And I think that that mentality is still current, that these are necessary costs for progress. But perhaps, the question that isn’t asked so much is well progress, but who is going to be disadvantaged for this? And who is there are certain groups disproportionately burying those costs.

Linda Yarr:

I’m Linda Yarr, here at the Sigur Center. You mentioned that the two engineers went to the Ghaghara River, you mentioned. So as you know, there is a quite pushback of civil society throughout Southeast Asia, the international rivers network, any number of organizations in Thailand, Vietnam, in Laos and elsewhere. To what extent do you see a connection between civil society and anti-movements in Southeast Asia and South Asia?

Sunil Amrith:

Very good question. And it’s something that is very close to my heart, in terms that it’s one aspect of the story they’re continuing to delve into. I think there are lots of connections, and they actually go back to the 1970s. One of the interesting things about this publication and other publications in this group is […].

Sunil Amrith:

Their first publication was called Citizen’s Report on Saving the Environment, and it was published in 1982. And it was a very short preface which says something that I find profoundly interesting, which is that their inspiration for that book actually came from Malaysia. And that it was actually going to Penan, which in ’70s was a real center of consumer activism, which by the late ’70s had turned into consumer/environmental activism that they got the idea because it had to be this consumer’s association of the lying cup, it had to be late ’70s published a citizen’s report of the state of Malaysia’s environment. Focusing particularly on deforestation, on how vastly the tribal peoples of Malaysia were being impacted by some of this development.

Sunil Amrith:

The same network around Penan, it morphs into something a little bit above the network. By the 1980s, they’re the ones who published Bruno Manser’s first book. I mean, Bruno Manser becomes perhaps the best-known environmentalist in the ’80s and ’90s. Really a spokesperson for the anti-localization movement. And in fact, he’s also first published out of Malaysia, and these networks that I think really are really important to the 1980s and ’90s.

Sunil Amrith:

I don’t know that the intent of the situations around the Indian environment that those links are as strong as they might have been on both sides. I suspect that through the 2000s these kinds of networks between civil society groups and trying to come together to see a shared government and were in search of these things.

Deepa Ollapally:

Deepa Ollapally from the Sigur Center, as well. But similarly we spent our possible alternative scenario to a securitization of water. And I will, I may suggest, that when you look at the China, India area that looks valuable in the area, one of the things that comes up is, of course, the Tibetan water tower, where all these rivers are in fact flowing from the headwaters. But then, when you look beyond the India, China and go further into Pakistan as well as Bangladesh, India is a midway area.

Deepa Ollapally:

So, the point is that when you look at relationships among these countries, your political relationships, because that’s what I look at. The idea that somehow China being the argument of control and having other forms of water, and so, if there’s dam building that constrains water to India, it’s also constrained to Pakistan and Bangladesh, who happen to be very good friends of China.

Deepa Ollapally:

So there is, I see a more complex set of relationships that then, perhaps the technical and political coming-together, where they only have to sort it out in a way that it could be an area of cooperation, rather than competition. How do you see that?

Sunil Amrith:

I mean, I think the goal of the whole confluence on that emphasis is sometimes neglect, but this is seen as a deal by both Indians and the Chinese are heavily invested in that construction in that part of the job. And I think that it’s precisely that level of complication.

Sunil Amrith:

It certainly led me not to conclude in my book that geopolitical conflict is the only way to get this to work out. I mean, I know some people are very strongly of that view, but I think I really agree with the theme dealing more around the geopolitical scenarios in that there are such complicated relationships.

Sunil Amrith:

Now, obviously, they’re also very much private sector investors involved. That’s one way we see things very different from that period of […] I was talking about when this was all state-financed or bank-financed, into such demand. I mean, now you have, of course Chinese engineering companies they’re such role models in the region, in parts of Africa. But there are also some private interests, too. So I think it’s become a much more complicated scenario than simply thinking about it in such a simple way.

Kristen:

Hi. My name is Kristen, and I’m studying history. I was particularly moved by your conclusion that […] provides the goods to alternative fuels to think about these problems, cultural to […]. Preservation issues in thinking about certainly the way that water has been controlled and incorporated into architecture, as these advanced use cases.

Kristen:

But also, the symbolic power of water, and particularly that the Indians should have a […] from the rivers. And I was thinking about river […] and the wonderful depictions that we have, and especially for it.

Kristen:

Did you find in any time of your research thinking maybe about what they do […]? In what ways have this cultural power, this sacred power of rivers, of these waters, has that come to play in these kinds of conversations about dam building or not?

Sunil Amrith:

That’s a wonderful question. What I’m struck by is that the sacred and spiritual power of the water is very edited in the 50s and 60s. And yet, somehow completely distinct from the conversation about dams, developers and the future. It’s not that one displaces the other, but that it’s that it’s sort of – so my colleague Diana Eck wrote that wonderful book India: A Sacred Geography, the chapters on rivers ends on the discussion: how could the Ghangra be the most revered and the most the future river of the world?

Sunil Amrith:

And she works through, without focusing a clear answer, she works through that question. And so the 50s, just when they’re building these big dams, there’s a massive complement out of the 1950s, which the burst after independence, which brings so many tens of millions of people to converge precisely on some sacred carrier river.

Sunil Amrith:

[…] in his last will and testament, he writes in a sort of spiritual sense about the Ghangra and about how he wishes his ashes to be buried there, not because he’s religious but because nevertheless, it represents the continuity within history. The narrative recalls that the dams are the temples of India comes this other side, there is this other vocabulary, there is this other way of thinking about water. Really in everyday life, the sacred power of the waters means as much as any of these infrastructure projects do to a lot of people in that area of existence.

Sunil Amrith:

And it’s sometimes when these things clash with one another, as I think they start to do in the 1980s that you see interesting ways of trying to address the relationship between the two. I think the main thing that’s happening is actually in the Indian courts.

Sunil Amrith:

So the National Green Tribunal of India actually recognized sacred groves, the preservation of sacred groves, as falling under the region of religion in the constitution. And there are ways in which even some decisions in Indian Supreme Court are almost personified nature in a way, not quite giving it rights in the way that some communities do it. But nevertheless, bringing in these arguments about the spiritual and sacred value of these rivers. It interestingly enough, is in the courts post-1908s that you see that tension really coming into form.

Harmony:

Hi, my name is Harmony Gale I’m a student at this school. The question I explore in my project, as you mentioned it, it is given a right and it is starting with the British power. Why do you think it’s getting that wide revival? I mean, we took the […] when in 2015 started and it began, but based along an opponent of it. There’s not opposition on it, and it started in 1917, and it’s a bit more […]. Why is that?

Sunil Amrith:

It really is an idea that just won’t go away. I mean, it was there in the 1870s, and there’s a moment in the 1960s where they start talking about it again. And I think some of it is just this profound sense that India is so shaped by the real inequalities of the water there, that it really does condense the waters in some of the driest places on earth. And that has clearly been something that’s wrangled in the minds, particularly of water engineers, of how we fix this?

Sunil Amrith:

I mean, I think there is that sense starting around the late 19th, early 20th century that the technology is there to do something about this. I think Madden makes the same comment in the 1950s, he says: “So much river in certain part of China, we need the gods to give us some.”

Sunil Amrith:

Across the ideological spectrum, I think there’s something profoundly attractive about this. I don’t think it will ever happen, and one of the reasons is purely that we think we controlled little today about water conservation and transform a way, but profound water advantage within it today. And I think that is what more than anything else, will stop a project like this. The common dispute has been going on since, depending on how you look at it, 1920s or 1950s. It continues to escalate to take on others, but nobody knows what they want.

Sunil Amrith:

How the river damming project will be governed on a integral level, is I think one of the things why it keeps running into trouble, and quite a large cost of it which is estimated now to […] dollars. And of course, there are profound concerns about being able to handle the impact and not taking rights. But even if those are featured in the compilations of both forms of government, I think these are these federal obstacles in this kind of project in India that are always a subject.

Speaker 8:

This is a question about – when I was in Chennai a few years ago, it seemed like there was a revolutionary water, rain water collection technology that was really changing the face of local water environments. Before actually having water for people in particular, on a regular basis was before, to buy it at a very dear price. Has it indeed changed things in […]? Has it changed things throughout India?

Sunil Amrith:

It has certainly not changed things throughout India. I think there are particular regions where there really has been a far greater investment in managing just thinking about water and I think Gangnam is one of them, Rajasthan is another. Meera Subramanian wrote a book called A River Runs Again, in which she investigated and interviewed some deeper […].

Sunil Amrith:

She investigated the revival of all water valleys in parts around Rajasthan, which did rely on these large technologies. But I mean, there is this about this romantic return to a […]. And some things are very new technologies, but then small-scale technologies, technologies that really do bring water to progress in ways that even the large dams often can’t.

Sunil Amrith:

And I think this is part she is very concentrated. I think it has a lot to do with particular political cultures, as well as particular other cultures, and Gangnam how the water activists since the 1990s have been pushing in this kind of direction.

Sunil Amrith:

They’ve got major public figures involved, including musicians and authors. And there’s a lot of brands about these things. But there is also an infrastructure of chance in Gangnam, which even if it was in decay, and it had been in neglect for a long time, some of which can be used in way to save Rajasthan. But by and large, if you read the work of the architect of this story, and […], it’s not happening.

Speaker 9:

I wonder if I can get you to go back to actually your starting point when your colleague asked you about the history of the monsoons about what sort of history. And I look at the title and you have Water and the Making of Modern India, and to be slightly provocative and push back, evocative national history in a way. And I wonder, what are the opportunities, but also the consequences of giving an ecological history with a national frame?

Sunil Amrith:

I’m not sure we really can. I mean, I think this is one of the things that gave this particular frame where a project and the book that this is from, one of the things that we again think is, we can’t write this story with a national lens. Not least because the monsoon – […] of monsoon is a dramatic phenomenon […] wants in science, wants specifically the story of monsoon sands from centuries of realization in the fact that monsoon has gotten a whole planet’s worth. And that is not something that can be delivered in the Indian subcontinent in say the 1850s or the 1860s.

Sunil Amrith:

But that it’s a real issue and that the issue and it’s effect on climate, as well as arguing on health. Every single one of these is regional trans-national sort of issue. And this is one of my challenges in starting to write my book. What would it mean to go to those certain areas, which there are a lot of people here.

Sunil Amrith:

We are so concerned with regions, how regions come about, what binds them together, where the boundaries are, how flexible their boundaries are. What would happen if we married that area of misconception with building an ecological conception?

Sunil Amrith:

So one of the things that started me on this whole project was the fact that in the social sciences, we all can agree monsoon Asia. There’s not one that we use. It’s one that colonial geographers used in the 1920s and 1930s, but it was a conversation. But that’s what is uncontroversially used by water scientists.

Sunil Amrith:

And, so that for me, really is one of the things that got me thinking about the monsoon, national distance of the monsoon, and how do you put scenarios that have perspective on this, with the focus on the fact that it is for a period in the 19th century the national states, which most tribes intervene to reshape the landscape of water. And yet, this is all what is seen in the boundaries.

Speaker 10:

I have a question about the politics of big dams. When I think about the politics of irrigation in India, I think of the Green Revolution: seeds, to wells, subsidies, and the farmer’s movements in the 1980s and 1990s that lead to a lot of that type of provisioning in that cultural sector.

Speaker 10:

Your talk portrays the politics of water; it’s very top-down, very technocratic. And I’m wondering if there is at all a broader politics of what public sentiment is with respect to dams? And how affluent parties have positions on dams, beyond just the Adivasi issue?

Sunil Amrith:

I think there absolutely is growing politics with water. I think it’s a very important politics of water. I think a lot of this does come down to who the groups that have benefited from these dams. And I think a lot of those farmers movements in the 1980s, 1990s were calling for more subsidies, for more two worlds, and I think as they were beneficiaries of this.

Sunil Amrith:

On the other hand, you have the farms who presented in the more recent past, the generation in un-irrigated parts of India, and who – maybe they want more irrigation? I mean, I don’t think this by any means had […] coming from the ground up. It’s not a story of top-down position dams. I think the opposition to dams is very specific and very pragmatic about the environmental level. You have those displaced by particular projects, like […], which of course, was huge at its peak.

Sunil Amrith:

But in some sense, there’s allowed nominees, because some of its supporters probably found that element of project might not have been in their interest, and water was not very often a major platform. But now, I think you will know this as more than I do about this perhaps, but I very rarely see water issues on election manifestos. Certainly elections have water like health, which is in fact both valuable but often politically invisible.

Sunil Amrith:

I don’t think most political parties have a major position on – I think most of the main political parties are more in favor of dams. Except those, who can make political capital out of a specific dam project, which perhaps […] constituents. And the politics of dams is also, I think in the interstate politics of dam building. So it’s a bit of a huge […] politics over the particular plans that the other side might have for those river waters.

Sunil Amrith:

So in that sense, there’s a politics of dams which has to do with control, which has to do with state boundaries, the state interests, the state rights. So I think every level of farmers movements to the geopolitical, which some of the other questions were suggesting towards.

Speaker 1:

We have time for one more question.

Joshua:

I’m Joshua […], I’m an undergraduate history major. So my question has to do with the economics of Pakistan, and taking time along their water scarcity crisis. Are there any lessons you can take away from what India’s doing, in how they’re working on the preservation of water? Anything specific that you can think of in how that might be something worthwhile […]?

Sunil Amrith:

I think Pakistan’s water crisis isn’t anything worse than India’s case. But there is measures that list them as the most stressed country in the world … Whether there are direct lessons from India, and whether those lessons would be palatable is another question. Particularly, given the rise in tension over the … in the recent months, that the Indians tried to withdraw the industry for the second time in the last four or five years.

Sunil Amrith:

I think there are conversations that are happening in other levels, going back to the earlier question. Indian and Pakistani environmental activists talk to each other. I think they exchange information. There are forums, neither in India nor Pakistan, where they can actually share the fact that some of these are very much shared problems and there are solutions to them.

Sunil Amrith:

I think there is a movement in Pakistan, particularly after the terrible floods of 2010, to think about the implications of climate change, thinking about the implications of that particular water infrastructure that Pakistan has become so dependent upon. And how it is in fact, the intensely engineered landscape that made floods so bad. And I think there is a movement within Pakistan, albeit on a small scale, that allows you think about perhaps other models. They may not come from India, I think there are many other places that re just as lacking.

Speaker 1:

Well, I think that takes us to the end of this evening’s formal program. Please, join me in thanking Sunil for his insights and really thoughtful questions about water in this part of Asia.