Hi everyone!

As the end of my summer language studies approaches, here’s an update on how we celebrated.

Sylvia Ngo, PhD in Anthropology 2025

Sigur Center 2021 Asian Language Fellow

Beloit College, Wisconsin, USA

Sigur Center for Asian Studies

At the Elliott School of International Affairs

Hi everyone!

As the end of my summer language studies approaches, here’s an update on how we celebrated.

Sylvia Ngo, PhD in Anthropology 2025

Sigur Center 2021 Asian Language Fellow

Beloit College, Wisconsin, USA

Hello everyone, welcome to my blog again.

Time had flown so fast, the study abroad journey has already reached its ending soon. Within these six weeks, I have learned so much from the professors and my classmates. Since it is an online program, I think the hardest thing when getting started on the program is time management. It is already hard to not be able to submerge ourselves into the “authentic” experience that we all wish for; on top of that, we are all overwhelmed with our personal life and keeping up with the classpath; thus, time management is the key to success in this program. There is a time that I want to give up sometimes or just simply don’t have that motivation to sit down at my table and start studying. In this blog, I want to show you a few tips that I used to motivate and stay focused on online learning.

1. Must-Have Items

The most critical materials I have with me are my Planner and my Notebook. The Planner helped keep me on track with all the deadlines, and Notebook keeps all of the learning material together for preview and review purposes.

Then, how do I use them?

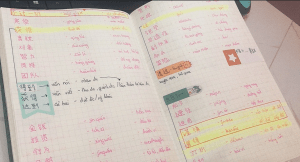

It is scientific proof that color-coding helped us work more proficiently. Therefore, I applied this method when using my Planner and Notebook to see things more manageable and remember the materials faster. For the most part, when using my Planner, I will first write down the due date for the work that needs to be done, and whenever I finish with that task, I will highlight green so I know that it is done. In addition to that, I always write down the due date earlier than it is actually due to avoid my procrastination self. With important tasks like project due dates, or testing dates, I will use a red pen to not miss them.

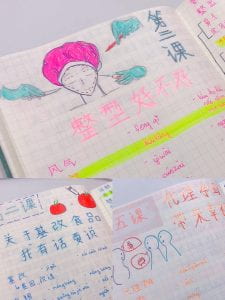

Since this is an online learning environment, it is limited to what I can do to enjoy my language learning experience; thus, I try to find joy when taking notes and viewing my notes as art. By doing that, I pushed myself to take beautiful notes and have more motivation to read and study.

(I tried to draw the lesion theme at the beginning of each note, this helped me have a deeper connection with the lesion and the material.)

Next, through my past study experience, I realized that I have always been stuck with one way of taking notes on vocabulary, which is simply writing them down in the order of [character – pinyin – translation], by copying the vocab down into my notebook and does not give the page any extra space, this had also limited my ability to connect the vocab to a bigger picture. With the pace of the TISLP, I learned that previewing is also the primary key to success in class. One of the most efficient routines that I learn work with me is before the class start, I will preview the content, copying down all the vocabs and grammar point, and make sure I give my note plenty of space so I can go back and fill them in later. During lecture time, I will try not to use my notebook but take notes on blank paper. Then after class, I can go back to my note and filling the empty space with the material on the paper. Doing this keeps me more focused during class time and helped me review the materials so much better. Again, I always tried my best to applied color coding when taking my note and keep the notes as neat as possible.

Traditionally, we always lean toward finding a quiet, familiar place to maximize our focus and study there. However, when learning a language, the emotional connection to the content is really important because we want to apply what we learn in real life, not just in tests and homework. Thus, changing the learning environment, study methods, and ways of practice is also necessary for learning a foreign language. Some strategies I applied to “learn and play” are daily text with my language partner, watching documentary films, listening to podcast, read Chinese comic books, etc.

In conclusion, even though this whole “study abroad” experience so far does not feel like a traditional study abroad experience, I did not let that get into my head. I had taken this learning opportunity seriously and try to get the most out of it. These intensive learning classes had provided me a chance to learn about the Chinese language and Taiwan culture and learn about many aspects that I didn’t know about myself.

Lyn Doan, M.A. Chinese Language and Culture 2021

Sigur Center 2021 Asian Language Fellow

National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan

(Featured image was taken during the last time I was in Taiwan. The picture is of Mt. Jilong and the photo was taken at Teapot Mountain).

Hi everyone, I am Matt Geason and I am a graduate student in the MA Asian Studies program at George Washington University. Currently, I am taking part in the Sigur Center Asian Language Study Grant. I sought out this opportunity to further improve my Mandarin Chinese ability to help prepare me for a potential career path at the Department of State. Because of COVID-19, I decided to take part in a language study program online through National Taiwan Normal University’s Mandarin Training Center (MTC). I have previously studied at MTC when I was studying Chinese in 2016 and had a positive experience in class and with the teaching staff.

For my current course of study, I am working 1-on-1 with a Chinese language instructor where I am focusing on speaking, listening, and I have a significant focus on reading. Additionally, this type of program has a customized syllabus where before the start of classes my teacher and I discussed the learning objectives, and proper material was allocated for the course of study. These customized learning objectives have greatly helped improve on areas of Chinese where I may have struggled more in the past but see significant improvement now. This is my first experience working intensively in a 1-on-1 environment and I think that there are considerable benefits to this, for example, my teacher and I have established a repour with one another and I think that this type of working relationship goes far to support my language studies. I believe that this is true because my teacher has been able to easily identify certain grammatical structures or vocabulary usage that is inconsistent and can target them and relate them with others I am stronger with to help me improve further.

Since classes started just a few weeks ago I feel my Chinese ability has steadily increased. The homework assignments involving news articles and short stories have challenged me to learn more characters and phrases at a much faster rate. Plus, at the start of each class, I give a short presentation regarding a recent news article. This is a new type of regular assignment that I am not used to from other Chinese courses that I have taken. This type of assignment requires researching an article, time spent understanding the article, and preparation for the in-class presentation and has helped me master new vocabulary and helped build my confidence in discussing new material. Additionally, outside of class, my teacher has assigned me Chinese Language TV shows to watch that I access through Netflix to also practice my listening ability and also learn more about how the language is used outside of the classroom.

In all the first few weeks of my course of study have been a lot of work but it has been very enjoyable being able to dedicate so much time to further my Chinese language ability. I am looking forward to the weeks ahead in my course of study and the further language advancement that I will be able to make.

Hello everyone, welcome to my second blog of the TISLP.

Lyn Doan, M.A. Chinese Language and Culture 2021

Sigur Center 2021 Asian Language Fellow

National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan

In pre-pandemic days, I imagined I would spend the second summer of my PhD program in Taiwan improving my Mandarin–which would also be an opportunity to talk to locals and get to know potential field sites for my dissertation fieldwork. But alas, with things still uncertain while I was applying to programs and with the recent COVID-19 outbreaks in Taiwan, summer 2021 in Taiwan was not to be. Instead I’m (remotely) attending a Chinese program hosted by the Center for Language Studies (CLS) at Beloit College (Beloit, WI, USA). As an intensive program, CLS promises a year of language studies in 7 weeks—delivered via a (virtual) immersion model. Virtual immersion is certainly not the same as being in Taiwan and still speaking, hearing, and reading Mandarin while navigating daily life beyond the classroom, but I hoped that through a model of virtual immersion, I could still become more comfortable with and instinctive in using Chinese. I want to take a moment today to reflect on what remote immersion looks like and how it’s going.

As one might suspect from the term “virtual immersion,” offline, we are left to our devices, free to converse and immerse in whatever language we want, but online, we are in a completely Chinese medium. Between our main class in the mornings, lunch with students at other levels, culture (and review) class in the afternoons, and one-on-one tutorials in the evenings, we are online 5 to 5.75 hours Mondays to Thursdays, plus about 2.5 hours on Fridays for reviewing and testing. Though there is the occasional fallback to an English word or phrase, teaching and participation is entirely in Chinese. At the third-year level, the inclusion of pinyin (English transliteration of Chinese characters) on materials is also minimal. In addition to attending classes, we have nightly assignments that include some combination of writing, speaking, new vocabulary, recitation, and grammar and vocab exercises. All of this together makes for a lot of Chinese in one day!

The Beloit CLS Chinese program can also be described as teaching/learning through a listening, speaking, reading, writing approach as we engage and practice all four of these skills while in the virtual classroom and while completing assignments. What I’ve enjoyed most about the way the program is taught is that our exposure to Chinese is not homogeneous. Take listening, for example: in addition to listening to instructors and fellow students, we also watch videos and movies, listen to songs, and listen to short articles. Between all this, the Chinese we hear is spoken by native speakers (who themselves have different backgrounds), heritage speakers (the category I fall into), and non-native speakers. In general when it comes to practicing the four skills of listening, speaking, read, and writing, the types of content we engage in and the activities we do are varied—some of the content we make use of is designed for Chinese language learners while others are not necessarily designed with learners in mind. Some of our online time is spent practicing new grammar, vocabulary, and structures, but a significant portion of our time is also spent on conversations and discussions. We also do role plays and play games. These more dynamic activities force us to be in the moment and to simultaneously listen, respond, and apply material we’ve learned.

Though virtual immersion can’t replicate the experience of living in a primarily Chinese-speaking locale, as it is being delivered by the CLS Chinese program, I would say that so far it’s doing a good job of preparing us students to be comfortable with our Chinese skills beyond the classroom and in a variety of settings.

Sylvia Ngo, PhD in Anthropology 2025

Sigur Center 2021 Asian Language Fellow

Beloit College, Wisconsin, USA

Hello everyone, welcome to my first blog of the TISLP.

Lyn Doan, M.A. Chinese Language and Culture 2021

Sigur Center 2021 Asian Language Fellow

National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan

The summer of 2020 did not go according to plan for me. I had planned to be in Pakistan and take advantage of the various archival sources present in the country. This time would also have given me the opportunity to interview bureaucrats from Pakistan’s formative years to understand how the state and society worked to conduct the Census of 1951 in the country. Unfortunately, a series of lockdowns, quarantines, and shelter at home orders halted most progress I could make research wise. This is an unfortunate situation that many researchers found themselves in from the start of the year. Even though I was able to get intermittent access to certain archives, it was not nearly enough to cover all the material that I wished to. In this blog, I will instead be talking about a few of the major archives in Pakistan, and how other researchers might be able to take advantage of the material within them.

The first of these are the National Archives in Islamabad. The National Archives of Pakistan are supposed to be the largest repository of official documentation in Pakistan and carry records from the Pakistan movement up to the 1980s (for now). The archives host a large collection of Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s private and official papers, and more from the leaders of the Pakistan movement. In addition, records from various ministries are available, though it is a tough task to convince the archivists to share this information with you. Though citizens of the country are entitled to these documents by law, the slow functioning nature of the archives means it is a long, and thankless task to get a hold of these documents. The easiest acquisition from the archives are definitely the vast newspaper and periodical records they keep, going back to the late 19th century in some cases.

The Punjab Archives nestled in Lahore’s Civil Secretariat provide a similar experience for researchers. The Punjab Archives are more digitally and organizationally advanced than the National Archives, and work is already under way in digitizing records from the Sikh period of the region’s history. Records date back to the 18th century, and include many official documents from the Sikh Empire, the British Raj, and in some cases the Pakistani government. It is harder to get post-independence documents here because a reorganization of the department has left many of these records unsorted, and unclaimed in various store-rooms. The library of the archives can be a useful tool for researchers, providing them with official documentation from various provincial and state level ministries from the colonial and post-colonial period.

By far the most organized archives in Pakistan happen to be in the National Documentation Center (NDC), also in Islamabad. Given their level of organization and digitization, gaining access to these archives is a touch harder than it is for other archives in the country. A registration, and security clearance is mandatory before any documents can be requested or viewed at the NDC. This repository stores documents from the Cabinet department, and the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO), and as of writing, documents have been digitized from 1947-1967, with the rest in the process. The Cabinet and PMO files give the clearest and most detailed view of policy discussion and making in the higher echelons of the Pakistani government, and many of these have proved immensely useful in my research thus far.

Pakistan is a tough place for researchers, and even more so for foreign researchers. There is little official guidance with regards to repositories of information, and it is only through your own networks that you get access to these various records. If there are any scholars who wish to work on Pakistan, I would gladly assist them on their venture and provide as much guidance as I can in this process. Pandemic or not, we are all in this together!

Rohail Salman, PhD History Candidate

Sigur Center 2020 Summer Research Grant

Pakistan