Whenever friends, family, and perfect strangers ask me why I love Indonesia so much, I find myself seeking an answer as multifaceted as the country itself—a task that is, quite frankly, impossible. I frequently describe the kindness of the people, the towering volcanos and kaleidoscopic reefs, the enchanting playfulness of the language. At times like this—when I can’t explain my infatuation in a few sentences or even a few days—I realize that is the reason I love Indonesia so much: its diversity defies description, no matter how many years I spend trying.

I first came to Indonesia to work as a PADI Divemaster during a gap year before attending GW, and fell in love with the people, language, culture, and underwater world—knowing that each of these terms encompasses a diversity beyond knowing. There are over 8,000 inhabited islands, 300 languages, countless indigenous religions and belief systems, and thousands of coral and fish species. I have since spent just under a year in total in Indonesia, returning again and again, seeking to understand a place so impossible to describe, knowing I have only just scratched the surface.

The beginning of this summer in Indonesia provides a perfect example of the intoxicating complexity of this place. I decided to fly out a few weeks before the start of my language program, knowing that I was about to begin dive hours a day of intensive Bahasa Indonesia training for eight weeks. So naturally, I headed straight for the ocean. I spent several days in Bali for freediving training, in the sea each day till the sun set over the gently smoking Mt. Agung (which would soon spew its ash and cancel hundreds of flights), listening to the tinkling of traditional brass instruments mixing with the evening call to prayer. Days later, I flew to the Raja Ampat islands in West Papua, returning to one of my favorite places on earth to follow up on research I conducted in the region in 2017. From traditional dances to magically ordained soccer games, from birds of paradise to mating sharks, one would be hard-pressed to find a place with so much to see. In no time at all, I was on a flight to Java, the largest and most populous island in Indonesia, driving through winding roads surrounded by rice fields that quickly turned into crowded cities that seemed to have sprung suddenly from the earth.

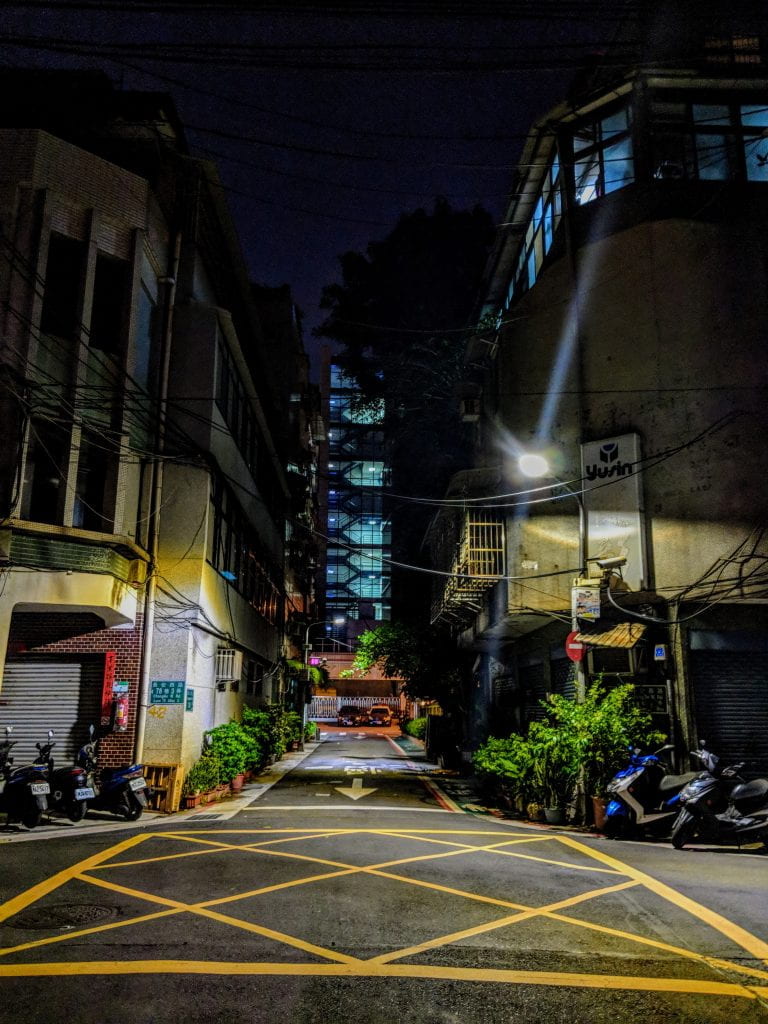

Far from the ocean and the places and people I had grown to love so deeply, I felt—for the first time in the almost 11 months I had spent in total in Indonesia—entirely out of my element. During the drive from the airport to my new home, I began to feel nervous. As the sky grew dark and neon shop lights flickered to life along the city streets, we pulled into the driveway and I saw the house I would live in for the next eight weeks. My host mother came into view in the doorway, her smile immediate, as she exclaimed, “Chloe! Selamat datang ke Salatiga!” Welcome to Salatiga.

Indeed, in the weeks since my arrival, to say I feel welcome is perhaps an egregious understatement for the joy that is finding a new home in every corner of this magical country. And I have only just scratched the surface.

Chloe King B.A. International Affairs 2019

Chloe King B.A. International Affairs 2019

Sigur Center 2018 Asian Language Fellow

School for International Training Indonesia, COTI Summer Studies Program, Indonesia

Chloe King is a rising senior in the Elliot School, majoring in international affairs with minors in sustainability and geographic information systems. She spent seven months in Indonesia in 2017 as a Boren Scholar, researching NGO conservation initiatives in marine ecotourism destinations around the country. A PADI Divemaster, her passion for protecting the ocean keeps pulling her back to Indonesia and some of the most diverse—and threatened—marine ecosystems in the world.

Taiwan is a must-come place for those interested in China. Upon arriving at Taiwan, I can’t help to be astonished by the closeness between Taiwan and mainland China in almost every important aspect of social life. The quiet and warm scenario of countryside reminded me of the villages of my hometown Zhejiang. The way in which people talk to children is also telling: on both sides of the strait the interactions with children is a means of education. On the train from Taoyuan Airport to Taipei city, my computer received the warm attention of a lovely boy with glasses, who obviously thought it was an advanced play station. When he tried to observe this wonderful machine more closely, however, his grandma came and told him that other people’s belongings should not be touched. Such educational experiences are very common for Chinese children in both mainland China and Taiwan, and similar patterns probably cannot be observed in other societies.

Taiwan is a must-come place for those interested in China. Upon arriving at Taiwan, I can’t help to be astonished by the closeness between Taiwan and mainland China in almost every important aspect of social life. The quiet and warm scenario of countryside reminded me of the villages of my hometown Zhejiang. The way in which people talk to children is also telling: on both sides of the strait the interactions with children is a means of education. On the train from Taoyuan Airport to Taipei city, my computer received the warm attention of a lovely boy with glasses, who obviously thought it was an advanced play station. When he tried to observe this wonderful machine more closely, however, his grandma came and told him that other people’s belongings should not be touched. Such educational experiences are very common for Chinese children in both mainland China and Taiwan, and similar patterns probably cannot be observed in other societies. Zhongtian Han, Ph.D. in History 2021

Zhongtian Han, Ph.D. in History 2021

Lexi Wong M.A. International Affairs 2019

Lexi Wong M.A. International Affairs 2019

Researching the history of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and associated topics is inherently difficult. First and foremost, every historian of the CCP has to deal with the limited accessibility of archival materials in mainland China. When I began my research trip in Nanjing and at the Jiangsu Provincial Archive, I was surprised to learn that, in contrast to common perceptions, the sources for the revolutionary period (pre-1949) was even more strictly administered than the early PRC period (1950s). In the beginning, they would not allow me to see anything and there is even no archival fond catalog available for the revolutionary period (while there are plenty for early 1950s). After some detailed inquiry about my research topic and suggesting some published primary sources at the archive, I was finally allowed to see three archival fonds, for which I’m truly grateful.

Researching the history of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and associated topics is inherently difficult. First and foremost, every historian of the CCP has to deal with the limited accessibility of archival materials in mainland China. When I began my research trip in Nanjing and at the Jiangsu Provincial Archive, I was surprised to learn that, in contrast to common perceptions, the sources for the revolutionary period (pre-1949) was even more strictly administered than the early PRC period (1950s). In the beginning, they would not allow me to see anything and there is even no archival fond catalog available for the revolutionary period (while there are plenty for early 1950s). After some detailed inquiry about my research topic and suggesting some published primary sources at the archive, I was finally allowed to see three archival fonds, for which I’m truly grateful.