Category: Sigur Center Summer Research & Language Fellows

The Sigur Center annually supports GW undergraduate and graduate students in pursuing summer research and language learning opportunities in Asia. Check out the entries below to read about Sigur Center Fellow adventures and experiences!

Summer 2018 Language Fellow – TMI & Baseball in Taiwan

Hello again. This is my first vlog! Zeynep Hale Teke, B.A. Applied Mathematics 2019 Sigur Center 2018 Asian Language Fellow Taiwan Mandarin Institute, Taiwan Hale is a rising senior studying Applied Mathematics in the College of Arts & Sciences department at GW. She fell in love with Mandarin…

Summer 2018 Language Fellow – The Freshness of it All

Sometimes I ask myself: What did I gain the most, so far, from my time here? I could, of course, take a shortcut and give myself the obvious answer. I could say that my Mandarin language ability improved tremendously. That I learn about 200 to 250 words a week. That…

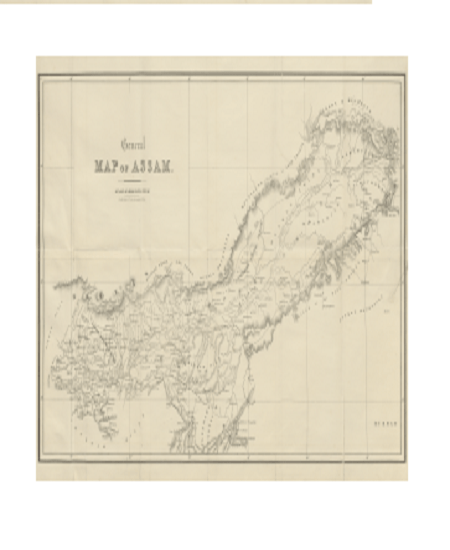

Summer 2018 Research Fellow – Finding an Early Map of Assam

Jane Bennet, author of Vibrant Matter, might agree with me when I say that documents in the archives have thing-power. Thing-power, to her, is “the curious ability of inanimate objects to animate, to act, to produce effects dramatic and subtle” (Bennet 2010: 6). A map is an inanimate object imbued…

Summer 2018 Language Fellow- Writing, Speaking, Listening, and Embarrassing Yourself in Chinese

Hello! Let me let you in on a secret: The secret to studying a language and speaking it is to utterly stomp your pride into the ground and make a fool of yourself on a daily basis. I’m proud to say that I have mostly managed to stomp my pride…

Summer 2018 Research Fellow – Rest in Peace Myitkyina: A Case Study in Local Initiatives and Provision of Public Goods in Myanmar

Myanmar Rescue – Kachin, locally known as Rest in Peace Myitkyina (RPM), is a Myitkyina-based rescue team in Kachin State, the northernmost state in Myanmar. It was first founded in 2012 and since then have become an integral part of the local communities across Kachin State. When the group was…