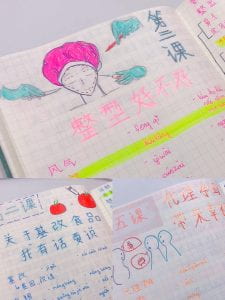

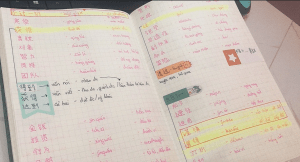

Eight weeks in the TISLP was definitely flown by quickly. These eight weeks are not only the journey of learning Mandarin but also the journey of learning about looking at life through different perspectives. Each week the students learn about a different controversial topic; we talked about familiar issues like Freedom of Speech or Plastic Surgery. Still, we also talked about topics that I never thought or even heard about, like Genetically Modified Organisms (GMO) or Nuclear Power. With unfamiliar issues like these, the language barrier is not the only challenging thing, but also the knowledge barrier is what the students struggle with. Taking the GMO topic as an example, this is a great topic because it was not much of a topic in the US since most US food is GMO base; however, it is a controversial topic in Asia, especially Taiwan. Thus, my classmate and I have to do much research on what is GMOs and what is controversial about them just to have a basic understanding of GMOs.

Every week’s topic was designed for the students to hear both sides of the argument, and at the end of the week, the students will pick their side and report why they choose their side. Since the class discussions are always controversial topics, the professor always clarifies that her main goal is for the students to practice language skills and not judge the students’ opinions about the topics. This had helped the students become more confident when sharing their ideas because, in this classroom, everyone’s primary goal is to practice Mandarin and not judging each other. Most of the time, the students will start out opposing (or supporting) the idea of the topic, and at the end of the week, their opinion is only more vital rather than changing. However, at the beginning of the GMO topic week, I started with opposing GMO products, thinking it is not natural or healthy for people. Surprisingly, by the end of the week, I had changed my side and choose to support the idea of GMO products. I learned that the problem of GMOs is not the product itself but how many giant corporations had taken advance of the GMO technology and made the product had a bad reputation. Through this chapter, I learned that the change of technology is not scary; what is scary is how people take advantage of technologies for making profits. Furthermore, people need to join together to contribute ideas and speak up about their concerns so the country’s government can change the law to protect people’s safety.

Through the TISLP, my Mandarin has not only improved significantly in all aspects (listening, speaking, reading, and writing), but most importantly, through my classmates, I learned that this world is very big and there are still many different voices, and for everyone to achieve common goals, mutual respect is fundamental.

At the end of the program, the students came together to answer an interview about the program. I hope you enjoy the interview.

Lyn Doan, M.A. Chinese Language and Culture 2021

Sigur Center 2021 Asian Language Fellow

National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan