In this video I share some information about ICLP and it’s competitors in Taiwan that I hope will be useful to students who are trying to decide where to study.

Caleb Darger

MA Candidate, Global Communications

Sigur Center for Asian Studies

At the Elliott School of International Affairs

The Sigur Center annually supports GW undergraduate and graduate students in pursuing summer research and language learning opportunities in Asia. Check out the entries below to read about Sigur Center Fellow adventures and experiences!

In this video I share some information about ICLP and it’s competitors in Taiwan that I hope will be useful to students who are trying to decide where to study.

Caleb Darger

MA Candidate, Global Communications

I recently finished my mandatory 3 days plus 4 health monitoring period in Taiwan. The process of me getting here this summer has been somewhat unique. I share these experiences in hopes that it will be useful to future students who may find themselves in a similar situation.

I initially applied to ICLP at National Taiwan University, but after some consideration I decided the MTC at National Taiwan Normal University might be a better fit for me, so I applied there too.

Right now, the only way to get into Taiwan as a student is either to be studying for at least 6 months or to be a recipient of the Huayu Enrichment Scholarship (HES). These two are not mutually exclusive. There is a lot of information on the internet about this scholarship so I won’t go into detail here, but suffice it to say you have to submit your application to the TECO (defacto consulate) for the region in which you live.

Unfortunately, in my HES application I had written that I would be attending ICLP, so when I won the award my records were sent to ICLP (Apparently the school you attend has to fill out some paperwork and work with the Taiwanese Ministry of Education to get your visa approved). After weeks of back and forth trying to figure out what was going on and get the different agencies talking with one another I finally discovered the problem. By that time, the semester was fast approaching, and MTC basically said “it’s too late, we can’t help you.”

I decided to turn back to ICLP (whom I had already informed I would not be attending) to see if they would still accept me and help me get my visa. ICLP was eager to help, they were communicative and professional. They assured me that I could start the semester online and join in person as soon as I made it to Taiwan and completed my mandatory quarantine and health monitoring period. It still surprises me when I think of how unwilling MTC was to help.

As expected, I started classes while still in the States. The time difference meant that I wasn’t done with classes until 2 am every day. After 3 days of that I finally made it to Taiwan, and I have been attending classes virtually since then throughout my quarantine. Being the only student attending virtually in my classes is not ideal, but my teachers have been accommodating.

Taiwan’s current requirement is 3 days plus a 4 day self-monitoring period. The rules are somewhat vague, but what is clear is that you have to stay at the same quarantine hotel for the entire 7 days. On the fourth day you can venture out but there are limitations on what you can do and where you can go. You also have to show a negative covid test (every 2 days) and fill out a form explaining why you need to go out and when you will be back.

My quarantine hotel was chosen by ICLP. It included a twin size bed, a tiny desk, mini fridge, and a bathroom. They also provide things like dish soap and laundry detergent in case you need to hand wash dishes or clothes in the bathroom sink. I paid about $700 USD for the week, and that included 3 square meals a day. Some meals were delicious, others just passable. I appreciated that most meals came with a piece of fruit—usually an apple, banana, or kiwi. The food was almost exclusively Taiwanese cuisine, but you are allowed to order from companies like Uber Eats if you want to mix it up.

The Taiwanese government has hinted at opening up the borders and loosening quarantine restrictions even further, but I don’t expect that to happen anytime soon. If you are planning to come to Taiwan this fall, I would prepare for the 3+4 quarantine policy to still be in effect.

Caleb Darger, M.A. Global Communication 2022

Sigur Center 2022 Asian Language Fellow

National Taiwan University, Taiwan

-Abhilasha Sahay[1] and Basit Abdullah[2]

Owing to the complex dynamics of gender-based violence, strategies used to mitigate its risk and occurrence need to be multi-faceted, involving various institutions and sections of society. Strict laws related to violence against women will not alone be effective until strong law-enforcing organs exist on the ground. As such, the police station that happens to be the first gate of the criminal justice system forms an important institution to prevent GBV (Human Rights Watch, 2017). Initial reporting to the police is a critical stage in the process of prosecution of sexual violence cases.

In the eyes of society, in general, and victims, in particular, the police form the main source of help for the victims of GBV. Thus, police attitude towards crimes can have a significant impact on the case trajectory, protection of the victim, and prevention of such cases in the future. The attitude of the police towards GBV, in particular, is essential in providing a sense of security and satisfaction to women seeking justice and protection from violence (Shakti, 2017). The negative attitude of police may impact the timely registration of complaints by the victim and influence their response to the situation. This shapes a negative perception of police, which in turn might discourage the victims from pursuing the case (Apsler, et al., 2003).

Police response to gender-based violence has been reportedly inadequate. According to a report on Need for Gender Sensitization in Police, the police response to cases of GBV has been that of initial disbelief of victim’s complaint, discouraging her from the pursuing complaint, aggressive and sexist questioning, delaying medical examination, and trivialization of domestic violence cases. According to a report titled ‘Barriers in Accessing Justice’ by Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) and the Association for Advocacy and Legal Initiatives (AALI), it is difficult to get an FIR registered over rape cases.

Besides other reasons, stereotypes about sexual crimes are also responsible for the inadequate response of police to cases of violence against women. While there are many factors behind low reporting of gender-based violence in India, including fear of social stigma, doubting the victim by police personnel remains a major factor (Status of Policing in India Report, 2019). Fearing the ostracization by police and the wider society, GBV victims do not report their complaints to the police (Joseph et al. 2017). The patriarchal beliefs held by the police officers discourage GBV victims to approach police for help (Dhillon and Bakaya, 2014). Survivors often suffer humiliation in police stations in India when they go to register the case, especially if they are from marginalized communities (Human Rights Watch, 2017). Further, cases of domestic violence cases are often considered family problems that have to be settled between couples (Bannerji, 2016). Victim blaming and tolerance towards domestic violence are also normalized. Stereotypes about women are often internalized by police in patriarchal societal structure, which they are a part of, and it is reflected negatively in their attitude in GBV cases (Jordan, 2004). Most officers in Indian police organization that comprises 90% of men are insensitive towards cases involving females (Kapoor, 2017). Patriarchal beliefs and gender-stereotyped expectations held by police affect the public confidence in the police and the criminal justice system (Tripathi, 2020).

The belief among police officers and broader society that false allegations of sexual violence are leveled has contributed significantly to the under-reporting of sexual violence cases (Lisak et al. 2010). However, rates of false reporting in GBV cases investigated by police low. Sahay (2021) estimates that the number of false cases out of total completed investigated cases by police vary between 5% and 20% in India.

Another salient issue with GBV case handling is the low representation of women in the police force. Historically, women were included in the police force due to increasing crimes against women and the need to deal with women culprits (Natarajan 2016). However, women still comprise only 7% of the police force in India according to “Status of Policing in India Report, 2019”. The opening of women’s police stations has led to increased reporting of crimes against women by 22% (Amaral et al. 2021). This is true around the world as the presence of women officers is found to have a positive correlation with the reporting of sexual assaults (UN, 2011-12). Higher reporting of sexual violence-related crimes and arrests made for such offenses are associated with a higher number of females at inspector rank in those places (Siwach, 2018).

A gender-inclusive police force will be helpful in dealing with gender violence cases effectively. It will help women, in general, get more access to police stations and give them a sense of confidence in reporting and pursuing their complaints. As such, increasing women personnel in the police force has many concrete operational benefits in dealing with GBV cases. However, the inclusion of women in the police force is not sufficient to result in a gender-sensitive and non-discriminatory attitude of the police. The internal organizational culture of insensitive and apathetic attitudes towards GBV victims has to be reformed in order to bring some change. Within the police, there is a need to ensure that officials are properly trained with skills to respond to and investigate the GBV cases effectively. The creation of specialized police services that can provide protection and assistance to female victims is an important step in that direction.

According to the Status of Policing in India Report 2019, police personnel in India largely lack gender sensitization training programs. Even those who report being trained on gender sensitization do not get such training frequently. A more sensitive police force can be encouraging for victims to freely come to police stations to report such cases and play the role of guide them about how to pursue the case after filing the FIR. The police officers should be given training in dealing with victims of gender violence and frequent teaching sessions organized for them sensitizing them about gender. Vocational training programs for police officers challenging their patriarchal beliefs should be organized for police officers (Tripathi, 2020). Both well-trained and gender-sensitive police force is needed to provide an enabling environment to provide justice to victims of gender-based violence. The cult of masculinity in the police force and the stereotypes they hold about sexual assault, harassment, or domestic violence call for both gender sensitization training and inclusion of women in the police force.

[1] Sigur Grant Recipient (AY 2020-2021)

[2] Research Assistant hired by Sahay

Abhilasha Sahay, Ph.D. Economics

Sigur Center 2020-21 Research Grant

George Washington University

References

Amaral, S., Bhalotra, S., & Prakash, N. (2021). Gender, crime and punishment: Evidence from women police stations in India.

Apsler, R., Cummins, M. R., & Carl, S. (2003). Perceptions of the police by female victims of domestic partner violence. Violence against women, 9(11), 1318-1335.

Bannerji H (2016) Patriarchy in the era of neoliberalism: the case of India. Social Scientist 3–27

Dhillon M and Bakaya S (2014) Street harassment: a qualitative study of the experiences of young women in Delhi. SAGE Open 1–11.

Human Rights Watch (New York, NY). (2017). “Everyone Blames Me”: Barriers to Justice and Support Services for Sexual Assault Survivors in India. Human Rights Watch.

Joseph G, Javaid SU, Andres LA, Chellaraj G, Solotaroff J and Rajan SI (2017) Underreporting of Gender-Based Violence in Kerala, India: An Application of the List Randomization Method. Policy Research working paper; No. WPS 8044; Impact Evaluation series. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

Kapoor S (2017). Culture change and law enforcement needed to make India safer for women.

Lisak, D., Gardinier, L., Nicksa, S. C., & Cote, A. M. (2010). False allegations of sexual assault: An analysis of ten years of reported cases. Violence against women, 16(12), 1318-1334.

Natarajan, M., 2016. Women police in a changing society: Back door to equality. Routledge.

Prasad S (1999) Medicolegal response to violence against women in India. Violence Against Women 478–506.

Siwach, G. (2018). Crimes against women in India: Evaluating the role of a gender representative police force. Available at SSRN 3165531.

Sahay, A. (2021). The Silenced Women: Can Public Activism Stimulate Reporting of Violence against Women?. Policy Research Working Paper 9566. Africa Region Gender Innovation Lab. World Bank Group.

Shakti, B. S. (2017). Tackling Violence Against Women: A Study of State Intervention Measures (A comparative study of impact of new laws, crime rate and reporting rate, Change in awareness level). New Delhi: Government of India, Ministry of Women and Child Development.

Tripathi, S. (2020). Patriarchal beliefs and perceptions towards women among Indian police officers: A study of Uttar Pradesh, India. International journal of police science & management, 22(3), 232-241.

-Abhilasha Sahay[1] and Basit Abdullah[2]

Across the globe, one in three women have experienced some form of gender-based violence (GBV) in their lifetime (WHO, 2018). The UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women defines GBV as “any act of gender-based violence that results in or is likely to result in physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty whether occurring in public or in private life” (UN General Assembly, 1993). GBV may exist in different forms including domestic violence, femicide, sexual harassment, rape, human trafficking, child marriage, online violence, etc.

GBV is widespread in India; according to 2015-16 NFHS-4, 30% of women between 15 and 49 have faced physical violence in their lifetime. As per data reported by National Crime Record Bureau, there has been a continuous rise in the number of GBV cases in past years. For instance, reported cases of crimes against women increased by 7.3% 2019 report as compared to 2018 (NCRB, 2019). With the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic and the subsequent lockdown, the increase in domestic violence cases also points to the huge gender disparity and vulnerability of women in India. India saw a surge in domestic violence with Covid-19 nationwide lockdown, according to data by the National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) (Times of India, 2020). The reported complaints of domestic violence cases doubled during lockdown according to National Commission for Women’s (NCW) data (Vora et al. 2020).

Owing to the socially sensitive nature of GBV crimes, several cases aren’t reported. In a recent global study – including 24 countries – only 7% of women who had ever experienced violence report it to formal sources such as police, medical facility and social services (Palermo et al. 2013). Similarly, it was found that only 3.5% of victims, according to 2015-16 NFHS-4, sought the help of police. A comparative analysis of NFHS 2015-16 data recorded by National Crime Records Bureau figures suggests that only a fraction (less than 1%) of sexual violence cases are reported (Live Mint, 2018).

According to NCRB report 2019, rape cases account for 10% of all crimes against women, and India reports on an average 88 cases of rape per day. Reported rape cases have almost doubled from 2001 to 2019 in India from 16,075 cases in 2001 to 32033 cases in 2019. Sexual harassment is another serious form of GBV prevalent in India. 21.8% of the GBV cases were reported under the category ‘assault on women with the intent to outrage her modesty (NCRB 2019). Cases of sexual harassment at the workplace have especially increased from 57 in 2014 to 505 in 2019. However, numbers are considered to be much higher than reported. According to a survey by Indian National Bar Association, 38% of the respondents reported that they have faced sexual harassment at the workplace, 69 % reported to have not filed a complaint with the management and dealt with it on their own due to fear, embarrassment, or lack of knowledge about laws and regulations. In 2013, the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act was implemented in India and the definition of workplace includes informal sector and domestic workers as well. However, since 95% of women are employed in the informal sector, the law exists only on paper due to its poor enforcement in the informal sector, according to HRW report 2020.

Homicides in intimate partner relationships remain one of the most prevalent causes of female mortality worldwide (Amin et al., 2016). Of all the murders of women, 38% are committed by their male intimate partners (WHO, 2017). In India, according to National Crime Records Bureau, female dowry deaths account for around 40 to 50 percent of homicide cases recorded annually from 1999 to 2016 (UNODC, 2018).

Domestic violence remains the top crime women in India face. GBV remains a challenge for society at large and the police system in particular. Despite the high prevalence, it is under-reported, which in turn contributes to high prevalence. Survivors of GBV may face several barriers to reporting such as shame and stigma associated with reporting such crimes, perceived impunity for perpetrators, and the normalization of tolerating such crimes in society (Palermo et al 2013). Gaps in criminal law procedures, gender stereotypes, and victim-blaming are considered as significant obstacles to survivors’ reporting of GBV, by UN Office on Drugs and Crime. Financial dependence of women and fear of consequences in the family of reporting are also some common hindrances to reporting domestic violence cases.

Since underreporting remains a major challenge in dealing with GBV, several interventions can help stipulate reporting of GBV cases in India. Special police units comprising women are likely to increase reporting of GBV as female officers are found to be more sympathetic, sensitive, and less authoritative in their attitude towards victims (Amaral et al., 2018). As such, female police officers provide a safe space for women complainants to share sensitive information about their cases. There should be efforts to reduce the stigma attached with reporting GBV, and the information of legal services for GBV victims should be disseminated. Public awareness using mass media can be an important step in this regard. Social movements, by raising awareness and sensitization, can also encourage GBV victims to report (Sahay, 2021).

[1] Sigur Grant Recipient (2021)

[2] Research Assistant hired by Sahay

Abhilasha Sahay, Ph.D. Economics 2021

Sigur Center 2020-21 Research Fellow

George Washington University

References

Amaral, S., Bhalotra, S., & Prakash, N. (2021). Gender, crime and punishment: Evidence from women police stations in India.

Amin, M., Islam, A. M., Lopez-Claros, A., 2016. Absent laws and missing women: can domestic violence legislation reduce female mortality?

Palermo, T., Bleck, J., & Peterman, A. (2014). Tip of the iceberg: reporting and gender-based violence in developing countries. American journal of epidemiology, 179(5), 602-612.

The Times of India. (2020). (Assessed 25th June 2020)

Sahay, A. (2021). The Silenced Women: Can Public Activism Stimulate Reporting of Violence against Women?. Policy Research Working Paper 9566. Africa Region Gender Innovation Lab. World Bank Group.

Vora, M., Malathesh, B. C., Das, S., & Chatterjee, S. S. (2020). COVID-19 and domestic violence against women. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 53, 102227.

WHO. 2018. Violence Against Women Prevalence Estimates, World Health Organization

With two years of one-on-one instruction (guided by Integrated Chinese‘s level 1 textbook) but a childhood immersed in Chinese-speaking environments as my background, my Chinese reading, writing, speaking, and listening skills have developed unevenly. Having a heritage background has largely been helpful in learning Chinese, but at times can be a hindrance. My listening skills surpass my speaking skills which in turn surpass my writing and reading skills. Before CLS, my Chinese was halting–there were times when I was speaking or writing when I would sense that the way I was phrasing something was (grammatically) wrong or awkward, but, unsure how to rephrase my thought, my efforts to speak and write could sometimes be slow and drawn out, with stops and starts. When I enrolled in CLS’s Chinese program, my hope was that through meaningful exposure to Chinese every day and actively working on improving with the help of formal instruction and feedback, I would be able to speak more intuitively and read and write more fluidly.

I was enrolled in the third-year class, which I found to be lively and engaging even with the long hours and steady workload. From Mondays to Thursdays, we had three and a half hours of class in the morning (with plenty of breaks!), followed by an hour of lunch with students from other levels, and then an additional half hour to hour of review/culture class in the afternoon. On top of this we had nightly homework and new vocabulary to memorize. Fridays were test days and the following Monday, we would start the cycle over again. Between the contact hours and the assignments and work we had to put in outside of these, there was certainly plenty of opportunity for Chinese practice every day!

Including myself, there were only 4 students in the class so there was both the opportunity and expectation that we be fully present and engage in Chinese. We each had different strengths, but at this level we were assumed to be proficient in the basics and to be able to navigate the everyday situations which were the focus in earlier levels. Of course there is always more vocabulary and grammar to learn, but the primary focus of the third-year course was to put these in service of honing our ability to express abstract thoughts and hold sustained discussions. Over the course of 7 weeks, we were not only regularly asked to share our opinions and thinking, but to elaborate and express ourselves in more than single sentences and phrases. Could we say more? What could we offer to back up our claims and flesh out our perspectives? At this level we were also asked to be attentive to writing in a more sophisticated way—to make use of transition words/phrases and conjunctions so that our sentences would flow and our compositions would have a sense of cohesion.

We spoke about childhood memories and the influence our upbringing had on us, evaluating and articulating opinions about leaders and people in general, the hardships and dilemmas that come up in life and how to respond to them, our dietary preferences and habits, the feelings that music and other situations evoke in us, societal issues, and achieving happiness. Our discussions were grounded in our own experiences, though we were often asked to also consider other perspectives. Since I’m studying Mandarin in preparation for a year-long anthropological fieldwork in Taiwan, I found the course content not only interesting but also incredibly relevant to my goals. Discussions around one’s background, experiences, influences, thoughts and feelings are exactly the kinds of conversations I hope to be proficient enough to have when I’m in Taiwan. Being able to have these kinds of conversations will help me connect with people, but they also speak to the anthropological interest in the richness of the everyday and in the specificity of lived experiences.

Overall, I really enjoyed participating in CLS. It was fast-paced and exhausting, but rewarding. I also enjoyed having the program length as window of time in which my main focus everyday was Chinese. Though this was not a fully immersive experience, the daily engagement in Chinese was helpful in building my confidence, which I believe is just as important as mastering grammar and vocabulary in being able to make use of my language skills. As I transition back into the academic year, I’m looking forward to being able to more fully appreciate Chinese dramas and extensive reading as a way to unwind while also practicing and further honing my language skills!

Sylvia Ngo, PhD in Anthropology 2025

Sigur Center 2021 Asian Language Fellow

Beloit College, Wisconsin, USA

Hello everyone!

This is my final video blog for my summer study program. I will be finishing my last class on Sunday and will conclude my 8 weeks study program.

In this blog, I am going to discuss some interesting places that have been talked about in my textbook that I think are fun places to visit when getting out of Taipei, and also I will provide some closing thoughts on my study program.

To watch the video please go to this link!

The Covid-19 pandemic has brought enormous difficulties for doing research on Asia. Since in-person visits to archives and field work has become more inconvenient, this blog post explores alternative ways to do research. Based on my experiences of using the “Data Platform of Documents on the Sino-Japanese War and modern China-Japan Relations (Kangri zhanzheng yu jindai Zhongri guanxi wenxian shuju pingtai),” (hereafter “Data Platform on Sino-Japanese War”) this blog post discusses the value of online databases for research on Asia.

Overview of the Database

Established in 2015, The “Data Platform on Sino-Japanese War” (bottom) was a project within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) center’s general initiative to promote research on the Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945). The database was directed by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, the National Library, and the National Archives Bureau. The funding for the database comes from National Social Sciences Foundation.

Most of the materials in the database are contemporary publications from the Republican period (1912-1949), including official documents, books, journals, and newspapers. By September 2020, the database contains more than 50,000 volumes of books, about 1,000 titles of newspapers, and nearly 3,200 titles of journals—more than twenty-five million digital pages in total.

The title of the database indicates that it is strong on Sino-Japanese War and China-Japan relations, but the sources in the database cover every aspect of Republican China. Therefore, the database can be helpful for any research that covers the Republican period.

Some Examples of Sources at the Database

One interesting set of sources I found at the database was the journal Resistance War and Communication (Kangzhan yu jiaotong), which was the internal journal of the Ministry of Communication during the Sino-Japanese War. The journal (bottom, copyright “Data Platform on Sino-Japanese War”) was published biweekly, and the database has all the issues from 1938 to 1942. The journal contains rich information on China’s wartime communications, including plans, conferences, and operations of the Ministry of Communication, as well as informed opinions on communication affairs. The journal is an example of the database’s strong collection of Republican period journals.

Another useful set of materials I discovered was the Military Administration Statistics (Junzheng tongji), a secret series compiled by the Ministry of Military Administration from 1937 to 1945. The series (bottom, copyright “Data Platform on Sino-Japanese War”) contains detailed statistics on every aspect of the Nationalist Army, including its combat and service troops, supplies and logistics, medical services, and armament industries. The series is a useful source to study the military aspect of the Sino-Japanese War.

Tips for Searching the Database

For searching of the database, I recommend use various types of keywords: thematic, personal, institutional etc. I also suggest sparing additional patience when searching for materials. The database covers a wide range and various types of materials, which are not sorted out in record groups as in an archive. Therefore, it might take more time to find useful sources.

Overall, the “Data Platform on Sino-Japanese War” is one of the largest online databases on Republican history open to the public. It offers an additional option for doing research during the pandemic. For other alternatives such as digital archives, please see my blog post “Doing Research on Asia during the Pandemic, Part I: Digital Archives”.

Zhongtian Han, Ph.D. East Asian History 2022

Sigur Center 2021 Field Research Fellow

China

The Covid-19 Pandemic changed everything, including academic research on Asia. The disruption of international travel to Asia limited access to archives, as well as the opportunity to conduct field work. In this situation, it is important to find alternative means to get sources and do research. Based on my experiences of using the Academic Historica Collections Online System, this blog explores the use of digital archives to do research on Asia during the pandemic.

Overview of the Archive

Established in May 1914 at Beijing, the Academia Historica (Guoshi Guan) was the central government institution responsible for compiling official history and collecting official documents. After 1949, the Academia Historica moved with the Nationalist government to Taiwan and reponed at Taipei in 1956.

The Academia Historica is responsible for managing the records of Republic of China Presidents and Vice-Presidents, as well as the records of a number of government institutions and prominent political figures. The records of Academia Historica cover the political, military, economic, social, and cultural aspects of the Republic of China. Therefore, they should be valuable for research on any topics of Republic of China history.

The digitization of Academia Historica records began in 2002. It was part of the Republic of China government’s general plan to digitize government records for public use. In 2016, the Academia Historica opened its digitized records to the public. By January 2019, the Academia Historica has made more than six million pages of digital documents available for public use. Since then, that number kept growing. The digital documents are searchable and open to download through the Academic Historica Collections Online System (bottom).

Some Examples of Records at Academia Historica

My experiences of using the Academic Historica digital records focused mainly on the Republican History (1912-1949). I found two collections of documents most valuable: the Chiang Kai-shek Collection and the Chen Cheng Collection. Chiang was the supreme leader of the Nationalist government and the Nationalist Army, while Chen served high civil and military posts under Chiang. The two collections include not only the personal directives and papers of Chiang and Chen, but also the official documents collected by or associated with them. Therefore, the two collections are comparable to U.S. presidential libraries in terms of the broad range of sources they contain.

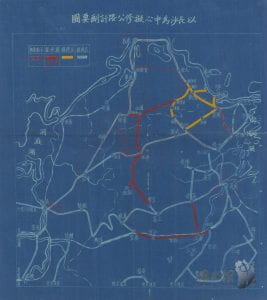

Some of the most interesting documents I discovered were those on the Wuhan Campaign (June-November 1938) in the Chen Cheng Collection. The campaign involved more than 800,000 Chinese soldiers and about 400,000 Japanese soldiers and was fought in central China. The documents in the Chen Cheng Collection revealed the elaborate communication networks on the Chinese side. These include a highway network that connected Hunan, Hubei and Jiangxi (bottom left, copyright Academic Historica), and an inter-province landline telephone and telegraph network in the three provinces (bottom right, copyright Academic Historica).

Tips for Searching the Records

The most convenient way to use Academia Historica digital records was through keyword search. To maximize the chance to find useful materials, I recommend using various types of keywords for any one topic: thematic, personal, institutional etc. It’s also helpful to pay attention to historical context and use keywords in contemporary use.

After searching by keywords, the results can be browsed either by the record group number or the starting year of the documents. When finding some useful documents, it’s also a good idea to browse other documents within the same record group. This often leads to additional useful materials.

Overall, the Academia Historica is probably the largest and best organized digital archive in Chinese language open to the public. It provides scholars with an alternative to in-person archival visits during the pandemic. For other options such as online databases please refer to my blog post “Doing Research on Asia during the Pandemic, Part II: Online Databases” on the Sigur Center for Asian Studies website.

Zhongtian Han, Ph.D. East Asian History 2022

Sigur Center 2021 Field Research Fellow

China

Hello everyone, I hope your summer is closing on a high note. My summer studies have been progressing well and I hope you all enjoyed my video on cooking dumplings.

Currently in my lesson we are talking about a lot of places that you can take a day trip to if you are already in Taipei. This blog I wanted to touch on some really cool areas that my lessons have recommended but also some areas which I have visited in the past while in Taiwan. It’s disappointing that I was unable to take part in language studies in Taiwan this summer, but having this language opportunity has really helped me improve my language ability and I am excited for the next opportunity where I will be able to go to Taiwan.

This area is very famous as a tourist destination where you can walk the winding streets of Jiufen and eat many kinds of street food in addition to eating at many great restaurants. Since Jiufen is in the mountains you are bound to find many hikes in the area that are of interest. My personal favourite hike is at Teapot Mountain. This is a fantastic hike that I think everyone who plans to head to the famous Jiufen area should take the time to make the short trip from Jiufen to Teapot Mountain. The views on a clear day are absolutely spectacular, as your view will be mountain summits against a backdrop of the open ocean. An easy place to start this hike will be from the Gold Mining Museum at the base of the mountain, from there you can take the trail about 35 minutes to the top. Alternately, you can drive up to just below the summit and walk the 5 minutes to the top to enjoy a great view. The best way to travel to this area will be by taking a train to the Ruifang train station and then taking a taxi to your intended destination.

This location from March to May has very beautiful views of the green vegetation that grows on the reef along the shore. The Laomei Green Reef is located north of Taipei along the north coast of Taiwan. It is best to visit Laomei Green Reef during low tide so that you will be able to see the vastness of the green reef and the view it has to offer tourists. The reef is a well known geological site due to the geological forces that have formed the unique landscape. Nearby this area, there is also a lighthouse that you can walk to and further enjoy the scenery and view. The Laomei Green Reef is not the most convenient location to get to. While there are busses that can be used to get there, the most convenient way to visit is by using a car or using a rideshare company; otherwise it might take too much time.

This tea house is not much of a day trip but rather a place to visit while you are busy exploring Taipei. I wanted to add this since I have really enjoyed my time while visiting. Wistaria Tea House is located near National Taiwan Normal University and Shida Night Market and is just a short walk from either. At the tea house, you have the option to have dinner or you can just relax in the tea room and enjoy the variety of tea and small snacks. One very fun part of visiting the Wistaria Tea House is how you will be educated on the proper preparation of the teapots and cups prior to enjoying the tea to ensure you are practicing the proper methods that enhance the flavor of the tea. The tea house is a fun educational experience and you will be able to enjoy the teas that are natively grown in Taiwan.

This excursion is south of Taipei and is actually in New Taipei City. The best route to take to arrive here is to take the MRT Green Line to Xindian Station and to take the bus or a rideshare company to the trailhead. The walk is not long and the scenery is very worth the time spent getting there. Once there you will see the buildings pressed up against the rock face and the beautiful waterfall overhead. Most places in Taiwan when hiking actually have a lot of stairs due to the frequent rain that often causes erosion. Therefore, the trails are usually nice and well maintained

Early in the program, we all received a package containing some swag as well as materials for our weekly cultural activities. In this video blog, I share the crafts we had the chance to learn and try for ourselves—all while continuing to practice our language skills!

Sylvia Ngo, PhD in Anthropology 2025

Sigur Center 2021 Asian Language Fellow

Beloit College, Wisconsin, USA