Hi again! This last week or so has been a whirlwind of activity, as directly after our midterm exam, we made our way to the train station to catch our sleeper train to the city of Datong (大同市), in Shanxi Province. Unfortunately, due to the recent severe rainfall resulting from a hurricane near the coast, the train tracks outside of Beijing were covered in water, and our train was delayed three hours while the tracks were cleared. We eventually made it on the train, and settled in for the six-hour journey. Many of us napped, some did homework, others played cards or chatted amongst themselves or with other friendly passengers, and though we arrived in Datong rather late, overall it was an enjoyable experience.

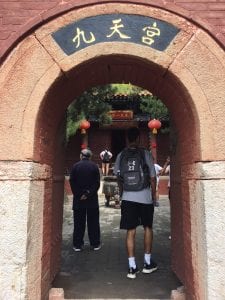

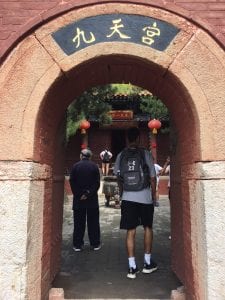

Our first full day in Datong was our busiest, we climbed Mount Heng, visited the Hanging Monastery, and admired the world’s tallest wooden pagoda. Mount Heng, or Hengshan (恒山) is the northern mountain of the Five Great Mountains of China, the most renowned mountains in Chinese history that were regularly the subjects of imperial and common pilgrimage. Hengshan is about an hour drive southwest of central Datong, and is littered with Taoist temples and shrines to mountain gods dating back to the Han dynasty.

We hiked from the parking lot to one of the highest vantage points on the mountain, although unfortunately didn’t have time to make it all the way to the top. The lush forests and nearby lake made for breathtaking scenery, and it was with regret (and rumbling stomachs), that we made our way down the mountain for lunch.

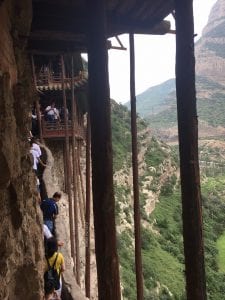

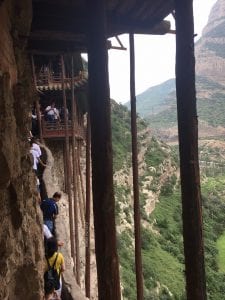

After, we visited one of Datong’s most popular attractions, the Hanging Monastery. The Hanging Monastery (悬空寺) clings to a crag of Hengshan, and is dedicated to three religions, Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism. According to legend, was built by a single monk, Liaoran (了然), in the late Northern Wei dynasty to appease the severe yearly flooding in the region.

Wooden poles drilled horizontally into the cliff face and vertically into the surrounding rock support the monastery’s 40 halls and pavilions. The temple is protected by the summit from rain and sunlight erosion, which along with its location well above ground level (and a restoration effort in the 1900s) has left the monastery remarkably well-preserved.

Our final stop was one of the tallest wooden pagodas in the world, again about an hour from Datong. The Sakyamuni Pagoda is a wooden pagoda built inside the Fogong Temple complex in 1056, during the Liao dynasty. It has survived several earthquakes and although severely damaged during the Second Sino-Japanese War, was quickly repaired, and today is the oldest fully extant wooden pagoda in China.

After returning to downtown Datong, my classmates and I, exhausted from the sightseeing, quickly ate dinner and went to bed.

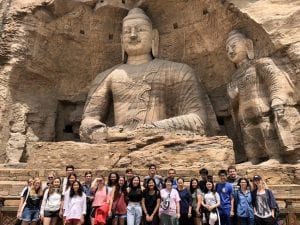

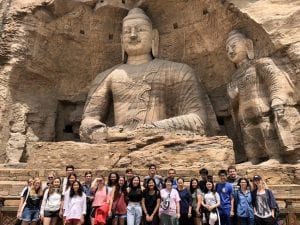

Our second day in Datong was our last, after breakfast we trekked out to our last site, the Yungang Grottoes, before boarding our return train to Beijng. The Yungang Grottoes (云冈石窟) are ancient and massive Buddhist temple grottoes, located about half an hour west of central Datong.

There are 53 major caves and 1,100 minor caves, excavated during the Northern Wei dynasty, which are today part of a large outdoor complex including several gardens and other historical buildings.

Since the caves and cliffs are sandstone, the grottoes and Buddhist statues inside have been exposed to heavy weathering over the years, especially the ones exposed to the open air. The wooden buildings in front of many of the cave entrances were constructed during the early Qing dynasty, built in an attempt to preserve the caves.

After viewing the caves, we took a short shuttle ride to another part of the complex for lunch and some light shopping, before packing up our things and returning to Beijing. The trip back was much like our journey there, with several rousing games of Uno and a serious game of weiqi being played along the way.

After arriving at our university, although some students had hoped to rally and head to Sanlitun (三里屯), an area known for its foreigner-friendly clubs and bars, most of my classmates and I promptly passed out, and woke up late on Sunday, ready to face the coming week (although less ready to do the homework most of us had neglected)!

Next weekend, I’ll travel with some classmates to Qingdao, in Shandong Province, so keep checking back for updates on the fun!

Katherine Alesio

Katherine Alesio

B.S. Civil Engineering 2020

Sigur Center 2018 Asian Language Study in Asia Grant Recipient

Minzu University of China – Associated Colleges in China Program

Alex Bierman, M.A. Security Policy Studies 2019

Alex Bierman, M.A. Security Policy Studies 2019

Zeynep Hale Teke, B.A. Applied Mathematics 2019

Zeynep Hale Teke, B.A. Applied Mathematics 2019

Katherine Alesio

Katherine Alesio

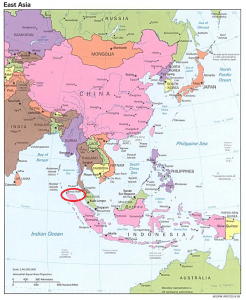

Jangai Jap is a Ph.D. Candidate in George Washington University’s Political Science Department. Her research interest includes ethnic politics, national identity, local government and Myanmar politics. Her dissertation aims to explain factors that shape ethnic minorities’ attachment to the state and why has the state been more successful in winning over a sense of attachment from members of some ethnic minority groups than other ethnic minority groups. She has won the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, and her dissertation research has received support from the Cosmos Club Foundation and GW’s Sigur Center for Asian Studies.

Jangai Jap is a Ph.D. Candidate in George Washington University’s Political Science Department. Her research interest includes ethnic politics, national identity, local government and Myanmar politics. Her dissertation aims to explain factors that shape ethnic minorities’ attachment to the state and why has the state been more successful in winning over a sense of attachment from members of some ethnic minority groups than other ethnic minority groups. She has won the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, and her dissertation research has received support from the Cosmos Club Foundation and GW’s Sigur Center for Asian Studies.