The Covid-19 pandemic has brought enormous difficulties for doing research on Asia. Since in-person visits to archives and field work has become more inconvenient, this blog post explores alternative ways to do research. Based on my experiences of using the “Data Platform of Documents on the Sino-Japanese War and modern China-Japan Relations (Kangri zhanzheng yu jindai Zhongri guanxi wenxian shuju pingtai),” (hereafter “Data Platform on Sino-Japanese War”) this blog post discusses the value of online databases for research on Asia.

Overview of the Database

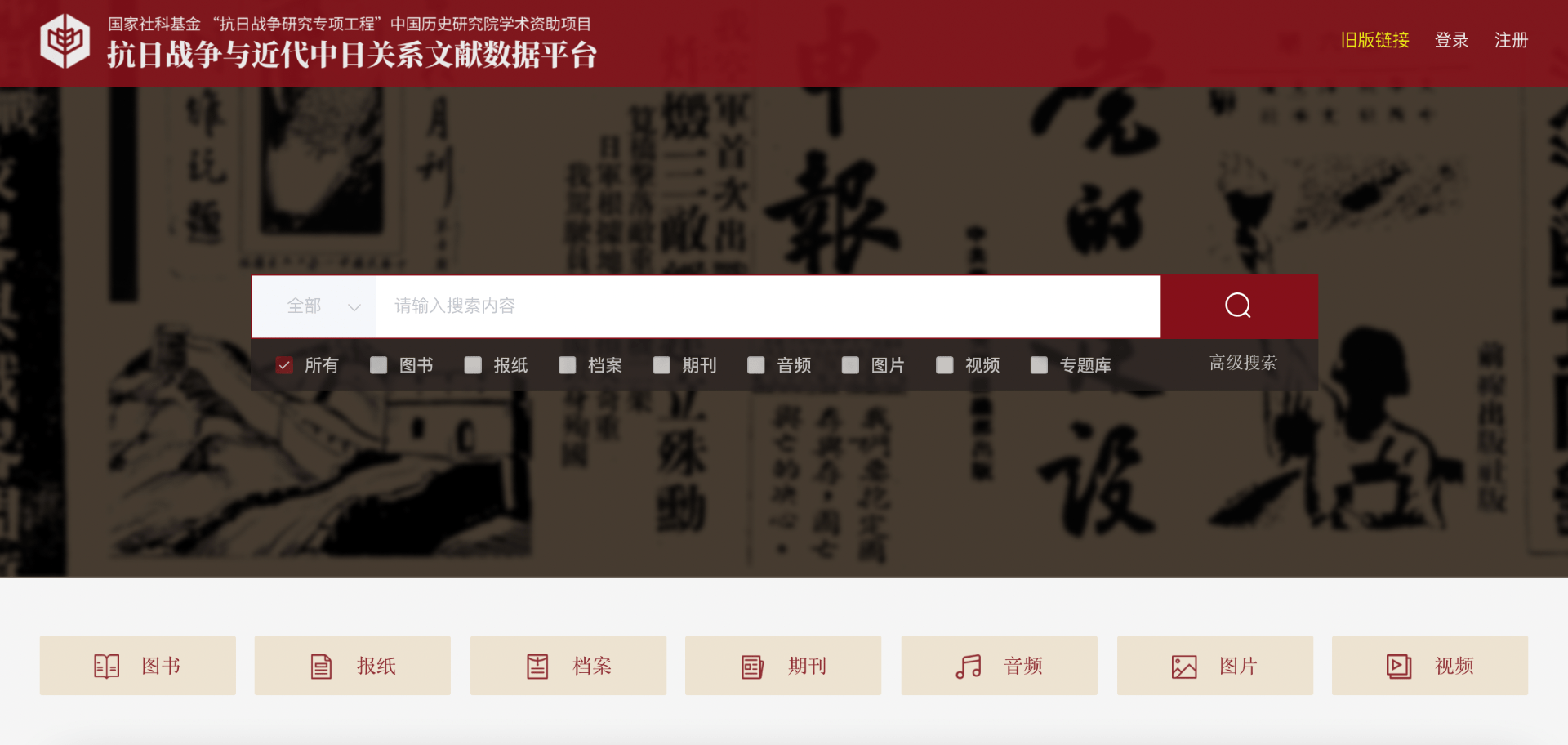

Established in 2015, The “Data Platform on Sino-Japanese War” (bottom) was a project within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) center’s general initiative to promote research on the Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945). The database was directed by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, the National Library, and the National Archives Bureau. The funding for the database comes from National Social Sciences Foundation.

Most of the materials in the database are contemporary publications from the Republican period (1912-1949), including official documents, books, journals, and newspapers. By September 2020, the database contains more than 50,000 volumes of books, about 1,000 titles of newspapers, and nearly 3,200 titles of journals—more than twenty-five million digital pages in total.

The title of the database indicates that it is strong on Sino-Japanese War and China-Japan relations, but the sources in the database cover every aspect of Republican China. Therefore, the database can be helpful for any research that covers the Republican period.

Some Examples of Sources at the Database

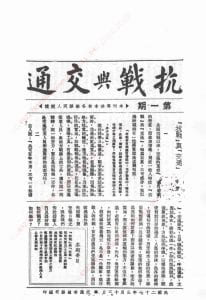

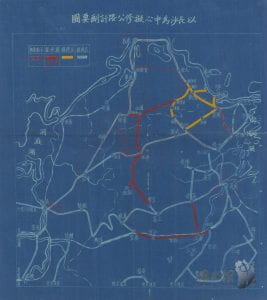

One interesting set of sources I found at the database was the journal Resistance War and Communication (Kangzhan yu jiaotong), which was the internal journal of the Ministry of Communication during the Sino-Japanese War. The journal (bottom, copyright “Data Platform on Sino-Japanese War”) was published biweekly, and the database has all the issues from 1938 to 1942. The journal contains rich information on China’s wartime communications, including plans, conferences, and operations of the Ministry of Communication, as well as informed opinions on communication affairs. The journal is an example of the database’s strong collection of Republican period journals.

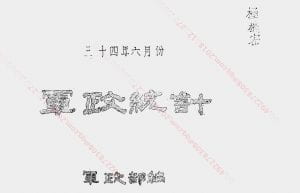

Another useful set of materials I discovered was the Military Administration Statistics (Junzheng tongji), a secret series compiled by the Ministry of Military Administration from 1937 to 1945. The series (bottom, copyright “Data Platform on Sino-Japanese War”) contains detailed statistics on every aspect of the Nationalist Army, including its combat and service troops, supplies and logistics, medical services, and armament industries. The series is a useful source to study the military aspect of the Sino-Japanese War.

Tips for Searching the Database

For searching of the database, I recommend use various types of keywords: thematic, personal, institutional etc. I also suggest sparing additional patience when searching for materials. The database covers a wide range and various types of materials, which are not sorted out in record groups as in an archive. Therefore, it might take more time to find useful sources.

Overall, the “Data Platform on Sino-Japanese War” is one of the largest online databases on Republican history open to the public. It offers an additional option for doing research during the pandemic. For other alternatives such as digital archives, please see my blog post “Doing Research on Asia during the Pandemic, Part I: Digital Archives”.

Zhongtian Han, Ph.D. East Asian History 2022

Sigur Center 2021 Field Research Fellow

China

Taiwan is a must-come place for those interested in China. Upon arriving at Taiwan, I can’t help to be astonished by the closeness between Taiwan and mainland China in almost every important aspect of social life. The quiet and warm scenario of countryside reminded me of the villages of my hometown Zhejiang. The way in which people talk to children is also telling: on both sides of the strait the interactions with children is a means of education. On the train from Taoyuan Airport to Taipei city, my computer received the warm attention of a lovely boy with glasses, who obviously thought it was an advanced play station. When he tried to observe this wonderful machine more closely, however, his grandma came and told him that other people’s belongings should not be touched. Such educational experiences are very common for Chinese children in both mainland China and Taiwan, and similar patterns probably cannot be observed in other societies.

Taiwan is a must-come place for those interested in China. Upon arriving at Taiwan, I can’t help to be astonished by the closeness between Taiwan and mainland China in almost every important aspect of social life. The quiet and warm scenario of countryside reminded me of the villages of my hometown Zhejiang. The way in which people talk to children is also telling: on both sides of the strait the interactions with children is a means of education. On the train from Taoyuan Airport to Taipei city, my computer received the warm attention of a lovely boy with glasses, who obviously thought it was an advanced play station. When he tried to observe this wonderful machine more closely, however, his grandma came and told him that other people’s belongings should not be touched. Such educational experiences are very common for Chinese children in both mainland China and Taiwan, and similar patterns probably cannot be observed in other societies. Zhongtian Han, Ph.D. in History 2021

Zhongtian Han, Ph.D. in History 2021

Researching the history of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and associated topics is inherently difficult. First and foremost, every historian of the CCP has to deal with the limited accessibility of archival materials in mainland China. When I began my research trip in Nanjing and at the Jiangsu Provincial Archive, I was surprised to learn that, in contrast to common perceptions, the sources for the revolutionary period (pre-1949) was even more strictly administered than the early PRC period (1950s). In the beginning, they would not allow me to see anything and there is even no archival fond catalog available for the revolutionary period (while there are plenty for early 1950s). After some detailed inquiry about my research topic and suggesting some published primary sources at the archive, I was finally allowed to see three archival fonds, for which I’m truly grateful.

Researching the history of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and associated topics is inherently difficult. First and foremost, every historian of the CCP has to deal with the limited accessibility of archival materials in mainland China. When I began my research trip in Nanjing and at the Jiangsu Provincial Archive, I was surprised to learn that, in contrast to common perceptions, the sources for the revolutionary period (pre-1949) was even more strictly administered than the early PRC period (1950s). In the beginning, they would not allow me to see anything and there is even no archival fond catalog available for the revolutionary period (while there are plenty for early 1950s). After some detailed inquiry about my research topic and suggesting some published primary sources at the archive, I was finally allowed to see three archival fonds, for which I’m truly grateful.