Figure 1. Tranquility in Takengon, Aceh.

There is a prevailing notion that violence is always a bad thing. Even when resistance to the state is justified, resistance should ideally be non-violent. However, political theorists are divided as to whether violence is ever justified, and if so, the conditions under which violence can be justified. For example, violence is typically understood to be justified under the condition of self-defense. However, what is included in the “self” of “self-defense” is typically up for debate: “the self” could be extended to include one’s family, community, political community, or others who are defenseless against tyranny. Moreover, there are often worse things than dying. Nevertheless, the non-violent bias motivates much empirical research on civil conflict.

One way the non-violent bias motivates empirical research is in the following research question: why do some people choose violent resistance as opposed to non-violent resistance? This was indeed my own research question going to Aceh, Indonesia. I asked: why did some Acehnese, given similar grievances, choose to become combatants, whereas others chose to become activists? The implicit normative assumption in this question was: why did some Acehnese choose “more moral” forms of resistance than others? The answer to this question of violent vs non-violent pathways, detailed in my previous blogpost, seemed rather banal: Acehnese who had access to GAM networks (Gerakan Aceh Mederka, the Free Aceh Movement) were more likely to join GAM; Acehnese who had access to student activist groups were more likely to become student activists. Many student activists, despite their adoption of non-violent tactics, were also likely to support GAM’s resort to armed resistance as necessary, and sometimes, even coordinating actions with GAM. One activist even described GAM combatants as like “heroes” (pelawan). For several activists, there was very little in their response that suggested a moral commitment to non-violence. This does not mean that the Acehnese I interviewed did not have some idea of what kinds of resistance was “moral,” but their idea of “moral resistance” did not hinge on whether one used violence or not.

So how can we understand moral resistance in Aceh? For many respondents I interviewed, there was a clear distinction between combatants who used violence as an act of revenge – an end in itself – and combatants who used violence instrumentally towards the protection of other Acehnese. I call the former “practices of revenge” and the latter “practices of pity.” No doubt many combatants used violence to seek out revenge, but many also used violence because they pitied victims of the conflict. Likewise, many Acehnese turned to activism because of the pity they felt towards victims of the conflict, but many were also looking for revenge through their activism. So what made resistance “moral” was not just the use of violence or non-violence, but how violence or non-violent activism was practiced – for revenge or for pity. Let me explain what this looks like, starting with combatants, then activists.

| Combatant | Activist | |

| Revenge | Violence as a weapon to punish and end in itself | Demands for accountability as a way to punish |

| Pity | Violence as a tool for helping Acehnese | Humanitarian efforts that help Acehnese |

Table 1. A Typology of Moral Practices of Resistance

In the case of violent practice of revenge, some combatants were clearly motivated by the desire for revenge – taking pleasure in killing as many Indonesian soldiers as possible. They were angry, even if they hadn’t themselves directly experienced any abuses by the Indonesian military. Notably, combatants looking for revenge were not interested in the preservation of life, especially civilian life. One ex-combatant I interviewed told me about how he missed his home village and was angry that there were seven military posts around his village, and then boasted how he had entered his village with his rifle anyways, which ended up with him getting shot at in the village. While he escaped unhurt, he had put his village at risk. Likewise, another ex-combatant I interviewed described how his unit had captured a local town for 14 hours – an important symbolic victory for his unit. The intention was not to hold territory, but to show their ability to drive out the Indonesian military from the town. When I interviewed civilians at the battle, many were terrified of being caught in the crossfire. Moreover, fourteen hours later, on Eid, the Indonesian military recaptured the town and subjected the civilians to intense security checks in case there might be GAM combatants hiding among them. These combatant practices of revenge prioritized winning battles or achieving symbolic victories over civilian life.

On the other hand, violent practices of pity look rather different. It may seem counter-intuitive that combatants may be interested in the preservation of life. Nevertheless, violence is not infrequently used instrumentally to minimize human costs. For one, such combatants emphasize the importance of keeping the fighting away from villages – which sometimes meant that they would forgo being able to go home. Another example, one ex-combatant explained how the most important role as a senior commander was to discipline his soldiers – including executing two of his men for raping a villager. Another ex-combatant explained to me that since the objective of guerrilla warfare is to demonstrate their presence to the Indonesian military, they would either choose non-human targets or shoot to injure, not to kill. In contrast to practices of revenge, the disposition of these combatants was always calmer, less angry, and more concerned about the suffering of others.

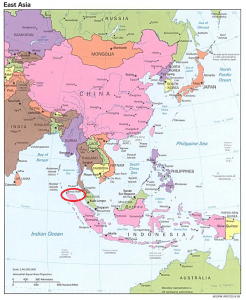

Figure 2. I would ask respondents what the definition of “peace” meant to them.

If there can be both moral and immoral uses of violence, there certainly can be both moral and immoral uses of non-violent activism. During my interviews, it was stark to me how different combatants could be from each other, and how different activists could be from each other. I found a similar pattern among activists – some were also motivated by revenge or anger and wanted nothing but to hold Jakarta accountable for past human rights abuses in Aceh. For example, one human rights activist explained how many activists would be so focused on extracting testimonies from victims in the pursuit of justice without realizing how the very act of sharing a testimony may cause victims to relive their trauma. Other activists were more practical and focused on what was best for victims. In Aceh, the term “humanitarian activists” was bestowed on those who were engaged in providing relief to internally displaced populations while also staying out of politics.

So, what counts as moral resistance need not necessarily be non-violent; and what counts as immoral resistance need not necessarily be violent. One can use violence and non-violence in moral and immoral ways. Just because the conflict is over does not mean that Aceh has attained lasting “peace.” Our lack of understanding of what motivates individuals to practice politics an all-or-nothing (revenge) as opposed to an open-ended dialogue undermines our ability to find solutions to both violence and non-violent forms of conflict. Understanding Aceh’s prospects for peace – not just the absence of violence, but the ability to negotiate and settle differences – requires an understanding of the (emotional) motivations (such as revenge or pity) how Acehnese practice violence or non-violent activism.

By Amoz JY Hor, Sigur Center Summer 2019 Field Research Grant Fellow. Amoz is a Political Science Ph.D. student at George Washington University. He researches on the emotional practices of violence and humanitarianism in Indonesia.

By Amoz JY Hor, Sigur Center Summer 2019 Field Research Grant Fellow. Amoz is a Political Science Ph.D. student at George Washington University. He researches on the emotional practices of violence and humanitarianism in Indonesia.