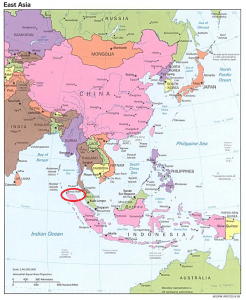

My fieldwork site is in Aceh, Indonesia. Aceh is at the western most province of Indonesia, and is known as the historical gateway to Indonesia – from economic trade, to cultural, political and religious influences.

This point is literally what is called “Zero Kilometer,” referring to the western most tip of Indonesia:

Aceh is probably most known by foreigners for being hit by one of the most devastating tsunamis in recorded human history – the boxing day tsunami of 2004.

The magnitude of the tsunami was met with one of the largest humanitarian responses in the history of humanitarian responses. Crucially (and the subject of a future post), the tsunami also brought an end to a 30 year-long civil war.

Below is an aerial photo of Banda Aceh (the capital) today:

(source)

The oval-shaped building at the centerpiece of the above photo is the state-of-the-art Tsunami Museum, also pictured below:

(Source)

This is not to say that Aceh has been “built back better” without complications after the disaster. Some aspects of the destruction are irreversible. Apparently, there was a land bridge to the island pictured below before the tsunami (the waterbody was originally a lagoon). Now, the village from the island cannot return to their ancestral land

Banda Aceh’s urban landscape is also unsurprisingly replete with memorials of the tsunami. Below is a picture of a boat that was swept on top of a house after the tsunami. It has now been preserved.

The landscape also includes structures such as the one below which people can run to in the case of another tsunami.

One challenge of such structures is that they are often left unused and thus lack maintenance because they do not serve other functions. This can be seen from the interior below:

From the sky, one can see the colored patterns of tsunami houses – houses built from the tsunami reconstruction. There are different colored patterns because different NGOs would reconstruct different communities’ houses, and is seen today as a symbol of inter-NGO politics that characterized the reconstruction.

Below is a street-view of a tsunami house. Some of these houses are empty today, especially those that were rebuilt in locations that are no longer inhabitable. For example, few live next to the coast worst hit by the tsunami – not only are many still traumatized by the ocean, but many of the aquaculture ponds (that were the main source of livelihood for the communities that used to live there) are beyond rehabilitation. I was told that it is not uncommon that such neighborhoods are inhabited by students who have moved to Banda Aceh for study – the ones who need cheap accommodation and have little alternative.

Although the boxing day tsunami grabbed headlines all around the world, the 30 year civil war (most of which was kept secret, and ended shortly after the tsunami) has gained less attention. Tellingly, in comparison to the tsunami, there is very little memorialization of the conflict, even though both ‘events’ registered over a hundred thousand deaths, with the latter occurring over a 30 year period, and thus leaving a much deeper impact on the Acehnese’s social pscyhe. Below is one of the memorials that have been erected to remember a torture center in Pidie, Aceh. It is a stark difference from the tsunami museum pictured earlier. Although such a memorial is surely sensitive to the central government, the Acehnese we talked to are clear-headed that remembering the conflict in a fair way is important to learn from their history.

Crucially, it is problematic to reduce the Acehnese identity to victims of either the tsunami or the conflict. Aceh has a rich heritage that not only extends much further back into history, but also much further into the present. In these narratives, the Acehnese are not merely victims, but actors in their own rights – fighters, activists, humanitarians, each with different ways of exerting agency over who they are and their future. If we pay attention, they also offer lessons for the world.

I will take up some of these themes in my upcoming posts.

Amoz JY Hor is PhD student in Political Science at the George Washington University. His research explores how emotions affect the way the subaltern is understood in practices of humanitarianism.