Indonesia, situated in the “ring of fire,” one of the most geologically active regions in the world, is prone to a wide range of natural disasters: volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, tsunamis, landslides, flooding, and drought are all regular occurrences in Indonesian life. The causes of many of these natural disasters also make Indonesia one of the most environmentally productive regions in the world, with nutrient-rich soil and coral reefs lush with fish, and for generations Indonesian people have thrived off these resources. However, both the unpredictability of the landscape and the seemingly boundless riches have combined to create an impossible dilemma: Indonesia is facing some of the fastest rates of environmental destruction in the world, perpetrated by its own population, and there is no solution in sight.

During all the time I have spent in Indonesia, I am continuously surprised by a general “wait and see” attitude in regard to both natural disaster and conservation planning. I have seen this as far east as Raja Ampat and as far west as Java, and this summer I decided to get to the bottom of it. I set out to understand how natural disaster planning and environmental conservation are intertwined in the minds of many Indonesians, particularly around the concept of “pasrah,” or surrender to God. Pasrah is profoundly linked to a wider state of passive acceptance that comes with many kinds of religious beliefs, particularly in Indonesia. It is a concept in which God possesses agency over human fate, in which all that will befall humans is predestinated. To me, this concept seemed entirely foreign; to most Indonesians, it is a concept that rules over everyday life.

In this regard, if it these events are all predestined, then attempting to plan for the future, to avoid natural disasters, is not only pointless, but an insult to God. As one scholar put it, planning in Indonesia is akin to atheism, a concept not only foreign but practically non-existent. This concept is widely seen throughout Indonesia in regard to natural disasters, from the eruptions of Mt. Agung in Bali to the tsunamis in Aceh, and it makes natural disaster planning difficult. Many people around Mt. Agung in Bali have been reported saying, “When the volcano starts erupting, that’s when we’ll go.” Communities often refuse to evacuate from the area despite official warnings, and planning for the event of an explosion has not improved significantly over the past several years. Is this a trend in Indonesian communities, and if so, how does it influence care for the environment? If all is predestined, that there is also very little humans can do to influence the natural environment around them—for better or worse.

Nearly 3,000 meters high, rising in between the Special Region of Yogyakarta and the province of Central Java, Mount Merapi is regarded as the most active of more than 100 Indonesian volcanoes and is among the most dangerous volcanoes on earth; the last major eruption in 2010 killed 347 people and caused the evacuation of 20,000 villagers. Despite the tragedy of these eruptions, recent research has shown that neither the villagers around Mt. Merapi nor the residents of Yogyakarta regard the eruptions as disasters, but rather a warning from the supernatural world.

The town of Salatiga, where my language program is based, is 23 km north of the base of Mt. Merapi, and many of its residents remember the eruptions of the past. Salatiga is the largest town in the high-risk area, with over 170,000 residents. I have interviewed and surveyed over a dozen residents during my time here, trying to understand what the concept of pasrah means to them, and how it influences planning for the future. While the survey sample was small, it became apparent that regard towards “pasrah” and a pre-determined future strongly influenced regard towards the environment. Those more inclined to believe that natural disasters were directly influenced by God were less likely to see humans as the cause of environmental destruction; those who did not view natural disasters as a result of God’s will were more likely to see humanity’s role in environmental degradation.

While pasrah is a concept that initiates from religious teachings, religion can also provide important lessons for overcoming the tragedy of the commons problem. The Quran states: “There is no joy in life unless three things are available: clean fresh air, abundant pure water, and fertile land.” There are over 750 verses in the Quran related to the environment, and Muslims are commanded to respect the environment and “Preserve the earth because it is your mother.” Likewise, the Catholic religion teaches respect for all creation, for “[t]he Lord’s are the earth and its fullness; the world and those who dwell in it” (Ps 24:1). These teachings were widely recognized by the people I surveyed, and added critical perspective to the context of pasrah in everyday life.

In May 2006, BBC news reported that in the villages around Mt. Merapi, “the local people do not listen to government officials. They listen to Marijan, the old “gate-keeper” to the volcano who enjoys an intimate spiritual relationship with Merapi.” It continues to be a struggle for the Indonesian government to prepare local communities for disaster, especially when people generally believe that whatever happens, it is the will of God. Likewise, in recent years Indonesia has experienced unparalleled rates of environmental destruction, from overfishing to deforestation to plastic pollution.

The government has begun several initiatives to both protect its residents against natural disasters and guard the future environment its citizens depend on. However, in order for individuals to realize their role in addressing these issues, religious institutions must emphasize the human responsibility for protecting the planet we live on. While pasrah is a concept that will always pervade Indonesian society, religious teachings can also inform people of their responsibility to care for their future. While the future may remain the will of God, the future health of the world’s environment remains in human hands.

Chloe King B.A. International Affairs 2019

Sigur Center 2018 Asian Language Fellow

School for International Training Indonesia, COTI Summer Studies Program, Indonesia

Chloe King is a rising senior in the Elliot School, majoring in international affairs with minors in sustainability and geographic information systems. She spent seven months in Indonesia in 2017 as a Boren Scholar, researching NGO conservation initiatives in marine ecotourism destinations around the country. A PADI Divemaster, her passion for protecting the ocean keeps pulling her back to Indonesia and some of the most diverse—and threatened—marine ecosystems in the world.

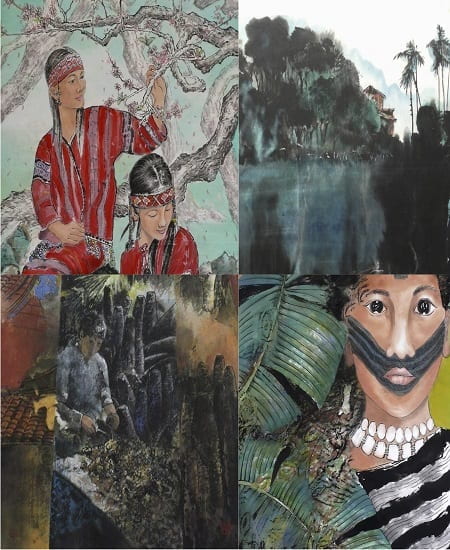

Jangai Jap is a Ph.D. Candidate in George Washington University’s Political Science Department. Her research interest includes ethnic politics, national identity, local government and Myanmar politics. Her dissertation aims to explain factors that shape ethnic minorities’ attachment to the state and why has the state been more successful in winning over a sense of attachment from members of some ethnic minority groups than other ethnic minority groups. She has won the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, and her dissertation research has received support from the Cosmos Club Foundation and GW’s Sigur Center for Asian Studies.

Jangai Jap is a Ph.D. Candidate in George Washington University’s Political Science Department. Her research interest includes ethnic politics, national identity, local government and Myanmar politics. Her dissertation aims to explain factors that shape ethnic minorities’ attachment to the state and why has the state been more successful in winning over a sense of attachment from members of some ethnic minority groups than other ethnic minority groups. She has won the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, and her dissertation research has received support from the Cosmos Club Foundation and GW’s Sigur Center for Asian Studies.

Katherine Alesio

Katherine Alesio

Alex Bierman, M.A. Security Policy Studies 2019

Alex Bierman, M.A. Security Policy Studies 2019